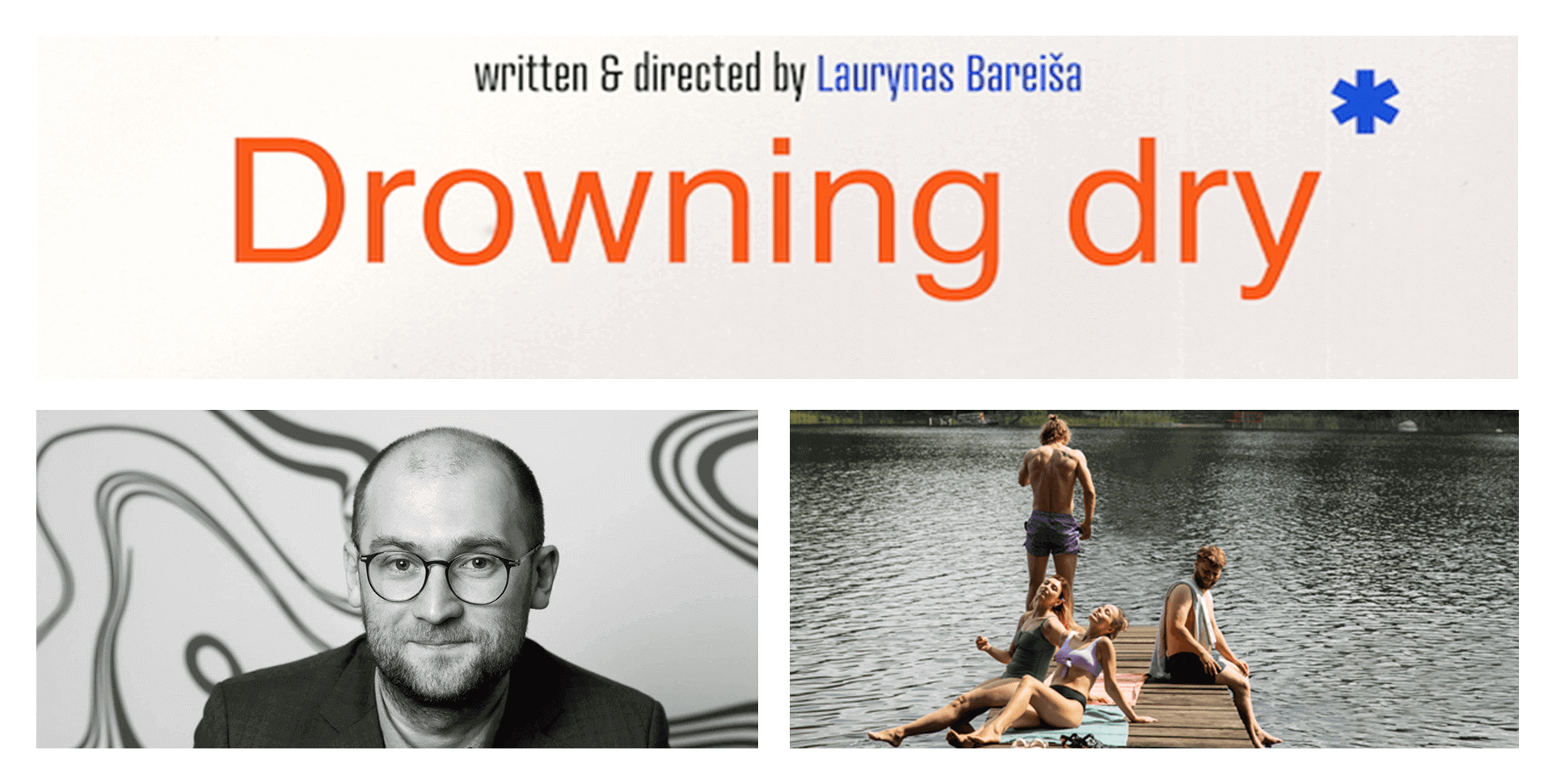

Drowning Dry is a 2024 drama film written and directed by Lithuanian filmmaker Laurynas Bareiša. The film was Lithuania's entry in the Best International Feature race for the 2025 Oscars. The following interview discusses the filming process, the director's experience working with the cast, and the film's fragmented narrative structure, with the latter leading to a consideration of how narrative structure may impact the viewing experience. The interview also considers the location/setting of the film, as well as the director's cinematic influences and future projects. Screening at the 2025 Santa Barbara International Film Festival.

Listen here. The following transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity:

Firstly, I'd like us to talk about the process of filming. How long did principal photography take, and how would you describe the process overall?

So it took me about 24-25 days to shoot it. We shot it in two big chunks, and we have one day in the middle. So we had a summer, a summer part which was like two and a half weeks, and the one week was by the script, the other one and a half weeks was a bit more improvisation and changing stuff, re-shooting scenes, and then we had the last half a week that was just special scenes, that was [the] car chase, the crash and fight scenes. So good. And then we had one shooting day after a month, which was with the table with the rotten food, and then we had the winter editions, one and a half weeks.

If you could, for our listeners, just to maybe describe a bit about the film. So, a spoiler-free kind of description of the film.

I always imagined it as a family drama, a vacation-style film where the family goes, and something happens between them. It's four adults, two sisters with their husbands and their kids. But in the end, it turns out to be bigger and connected to a wider life of theirs.

Yeah, actually, it reminded me a little bit of the film. I don't know if you've seen the film by Lucy Kerr, Family Portrait, it's very similar. It's not the same kind of narrative, but the approach is quite similar.

Yeah, it seems to be a classical drama. People in a house alone.

What was it like working with the cast? Also, another question attached to that about just working with the cast generally — what do you value most when casting performers and collaborating with them?

I always cast people who I feel comfortable with, and they feel comfortable with me. First of all, It's [a] human-like relationship, we connect, or we don't connect. So if we don't connect — even though I feel that it may be a good choice for the actor, for the character — I usually pass because it's a long process, and usually I like to change, adapt [and] adapt to the character. So it's easier for me to find someone I'm good at spending time with, and then develop relationship[s] and character[s] and maybe change some things so that the character is better suited for them. Yeah, half of my cast usually is people who have worked before. For this film, I also was a cinematographer and a director on set. So it's usually a bit of a different process when I can stand their way of filming, so I need the cast to be able to adjust and not be too overprotective of their own process, so because it's kind of a different thing for me. I rewrite in the evenings, [and] I edit. So I want to have them comfortable with me. So yeah. First of all, I connect to a person.

I've seen that you'd worked with some of the cast before as well. I was wondering if you could tell us a bit about how those relationships and those collaborations have developed across different projects.

Yeah, so there is Paulius [Markevicius], we met when we were at film school. He was studying acting. We developed our relationship through 10 short films and films [that] I worked [on] as a DOP, and he was an actor. So yeah, we just started as friends.

There's also Gelmine [Glemzaite], whom I worked with on some films as a DOP, but I also admire her as an actor. I don't usually become friends with my actors, but I usually try to always have them in a comfortable position on set and during the preparation process during rehearsals. This relationship — even if we don't reconnect between films when they come back to the films, we're always very positive about the process, and I know I tried to keep a good relationship with all of them.

Clearly, a positive relationship if they want to come back to work with you and keep collaborating with you as well. I'm a teacher, and what you were saying there resonated a bit in terms of how you need to have that perhaps a professional boundary, but also, at the same time, you want to have a good rapport because you're going to get the best out of the people you work with, right?

Yeah, but it comes from my experience because we also extend this relationship to our crew. [Our] producer does the same thing — Klementina Remeikaite — she uses the same rules for our crew, so we always work mostly with the same crew, and we try to keep our relationship good with them. So they want to work with us on all of our future projects. When you have more time, it's easier to collaborate than the next film because we know who you are, and you save a lot of time. And with actors and crew also, there's less to explain, less to catch up to, and it's very useful.

So Drowning Dry has a fragmented narrative structure. What inspired you to use a more non-linear storytelling approach, and were there any challenges you faced in crafting that kind of narrative or storytelling?

Yeah, because Drowning Dry was always connected to this — how do I analyze this almost tragic memory, like something happened. And for me, memory is always about repetition. Coming back is doubling; you see it once in real life, and then you remember it. I always knew that it [was] not going to be a linear structure because, for me, it's important to analyze and to come back to this event. So, in order to come back, you need to have a place where the time shatters — where's the first jump? Because then, you get into a film. I always knew that I wanted it to have it not be too early — the time jump is at 40 minutes, and it's kind of a challenge because the whole film shifts. Structurally, when writing the film, and trying to find this good moment to jump, not to be too early, but not also to be after one hour or where the film is too set, just like concrete, if it's set or not set, and it's not just the right moment. So yeah, that was kind of a challenge. And then how, how do I come back? It opened for me when I found that this moment, when the time changes or the time shatters, is the moment when the trauma for the older sister happens. She has panic attacks, and here was a moment where it started. I found that moment and based it on it. And also these literal connections from water to water, from ambulance to ambulance, these time jumps where there's connections, not in time, but somehow in meaning or in some literal details. So, I jumped through that, and for this, I tried to connect to these parts.

I'm interested to hear a little bit more about that jump and what effect you hope that would have on the spectator. So what kind of effect on the audience was a hope for you?

Yeah, I wanted to have an effect that this moment was the moment where I thought would be the most difficult for a spectator because it's a moment where you lose all the grounding. You thought that it's going to be this film where it's in one place and it's about the family and inner dynamics, and then, the time shifts, and you lose your ground, and then you have to find everything. So in my nightmares, I thought that maybe half a room leaves and everybody says, fuck it, it's a stupid film. But then also, it's a translation of what this feels, this [is] traumatic because I experienced something similar, and I wanted to translate it into cinema language; when you lose this touch. I wanted it to have a very, very hard jump, like in Nicolas Roeg's films; it used to be very direct editing. This has this meaning for me, as when you have this kind of event that always pushes you towards it, some you maybe forget it, you maybe move on, maybe nothing happened because here — the girl didn't drown, nothing tragic happened, but still the moment has this heaviness inside your head.

I wanted to have this aggressive effect towards the audience. That's why it's so sudden. And that's why it had to be later, because if it's after 10 minutes or 15, then you're still in the moment of realizing what the film is. When it's at this moment, I think it becomes a bit more hard to stomach. For me, I want the film to mutate, to always change. Not to have this sense of security as a viewer in order to translate what the film is about.

Yeah, I think it makes it more effective and powerful as well. You mentioned Nicholas Roeg there, so I wondered if you could talk to us about some of your cinematic inspirations and influences, and did any of those, I know you mentioned Roeg there, but did any other shape or inform the making of Drowning Dry, the stylistic approach, the narrative, etc.?

I like Roeg because I like how he approached editing and how it made you feel. But also from filmmakers, even when I also teach students, I always say it's very, it's very dangerous to have literal references, visual[s] for films, because everybody works in different contexts, in different time and space, and even technologies. Usually, I like to be inspired by the feeling, or by how emotionally I feel towards the films, and then be conscious that I will be going to [be] assembling the film from what I have, from what I see, and what I work with.

So I don't usually have visual references; I have more of these ideas or stuff that I like because Edward Yang is a big influence on me. I love this Taiwan New Wave — I don't know what we call this period in the 90s, [and] late 80s when we had these filmmakers [Taiwan New Cinema]. And also, Takeshi Kitano is a big influence. I love how he approaches editing and thinking through film — how he just skips through time, and then you get, you have to follow him. He doesn't sometimes; the film runs in front of you. Usually, I tried to come on set. And especially on this set, I wanted to come with a bit of a free mind in order to be able to adjust and use my intuition more because I wanted the film to be shot from this perspective of remember[ing] time. You're not in it; it's not first-person time; it's more like a third-person viewpoint. And I always wanted to adjust. That's why I didn't take a camera operator or a cinematographer because I didn't want to explain some choices I made. I just wanted to do that shot, then maybe try a different shot, and just have this decision in the moment because they have a good relationship with actors, the crew understands it, and we are always prepared. I always prepare for change. I always give my set designer options where I maybe will go. We have a primary option. We have a shot list and everything, but we also have options for them to be prepared, if maybe something changed.

What I'm getting from that makes it more of an organic process as well. And you mentioned about the third-person viewpoint. While watching the film, it reminded me of Michael Haneke and his films. Those kinds of third-person viewpoints were slightly distant sometimes from the characters.

Caché and Benny's Video, especially. Yeah I loved those films when I studied. Watched a lot of them.

Yeah, that's a great filmmaker, and thank you for talking to us about that, as well as some influences, or maybe not those conscious influences within your organic process. So my penultimate question is about the setting and the lakeside country home, which you could argue serves as quite a poignant backdrop for the story. How did you choose that location?

That was actually quite a difficult part of the film because usually, it's not a standard country house in Lithuania, because most of these country houses are very ethnographic and very rustic. And we wanted to have this place that is between a house and a country house. I wanted it to have a bit of a place near the lake, but it's also quite secluded to have more of a universal feel for the house. So it's not a standard Lithuanian country house. And then we had, it was better challenge finding it. It had to be just enough country but also not too detailed for me because then it would have been too much character for a place. So I tried to look for it a lot because most of the country houses are reminded of the Middle Ages and all these details, like cartwheels. So it was a good one. It was quite a challenge.

So I'm just thinking, I'll just dig a bit deeper on why a country house. So why was that your choice for what happens in the narrative? What stood out to you about having it set there?

Yeah, I wanted it to be like a bit of [an] idyllic place near the lake. All of my memories from summer and my parents are always near the lake, and it's a universal time and place, like a vacation place. Usually, vacations are near a lake, so that's why I wanted it to be a bit misleading like it's going to be something just with a house or something with a positive relationship toward the summer. A bit idolized. That's why I wanted it to be in this pretty place.

I suppose it kind of exaggerates that juxtaposition between tragedy and then the idyllic setting.

Yeah, especially the first evening, it's most of it like it's the sun is setting, it's golden hour, and it's like it's quite a nice place to be. In a good way [to] prepare for the second day, I think it gets your mind off everything.

Okay, my final question is about future projects. Are you able to tell us about any future projects that you've got coming up?

Yeah, I'm actually now editing a film. But as an editor — it was directed by my friend, so I'm working on it. And I'm writing also. We had a project application for pre-production. I'm working.