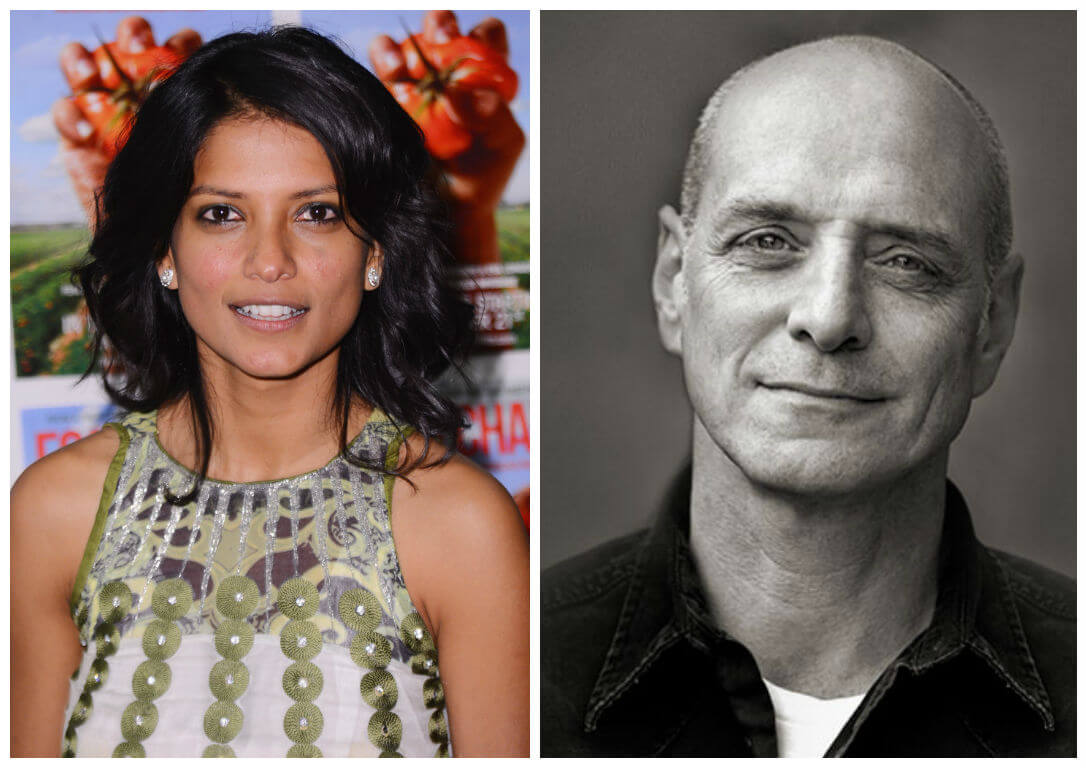

Ambitious multimedia film installation the bomb (2016) will premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 23. The film is intended to immerse its audience in the experience and reality of nuclear weapons, and will be shown on a 360-degree screen while music group The Acid performs the score live in the center of the theater. I recently had the opportunity to discuss the conception and creation of this unique film with its producers Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser.

Check back in late April for my review of the bomb.

Where did the idea for the bomb come from? Was the impetus to create the project personal, political, both, neither?

SK: For some time, I had been thinking about challenging the one-way, one directional experience of viewing. Whether it’s a film, a theater performance or a live music show — these are always projected at you. But what if you were in the center of the story? How would your perception of it be different, by simply changing the way you experience it?

It was around this time that I was reading Command and Control and had this clear, strong and urgent response to want to create a deeper, visceral experience of nuclear weapons, so people could feel the gravity and reality of living with these weapons.

Do you see the bomb as an extension of your book Command and Control? A companion piece? (Directed to Mr. Schlosser)

ES: It’s been deeply rewarding, over the years, to work with artists who've been inspired by something in my work. The book may be the starting point, but what emerges from it ultimately proves to be a very different thing. There's no single way to address a subject. My book, Command and Control, is one approach. The documentary based on the book that Robby Kenner has just made, also premiering at Tribeca, is another approach.

And what Smriti and I have done with the bomb is wildly different from both. My book Fast Food Nation encouraged others to write about and make films about our food system, in their own voices, using all sorts of techniques. I hope Command and Control can have the same sort of effect.

Was the film always meant to be presented as a multi-media installation? Did you ever consider making a more traditional documentary?

SK: From the outset my instinct was that for people to truly wake up to the nuclear reality, that the bomb needed to be felt rather than passively seen. On a personal level, I connect with art and film that is bold and poetic. And I’ve grown up in an environment with scientists and engineers in my immediate family, so often I think of how to make complicated concepts relatable.

You both worked together on the film Food Chains. Is this where you first met? How, if at all, did this shared interest inform your decision to co-create the bomb? Did you discover any other areas of overlap while working together?

ES: I met Smriti while working on Food Chains. I found her to be a remarkably gifted producer. Now that we've worked together on a second project, I've learned that she has a great career ahead as a director. She has a terrific eye, phenomenal discipline, a willingness to go all-out on behalf of a bold idea, and great taste in music. We instinctively agree, far more than we disagree, about creative issues. That's what made our work on the bomb possible. She also has a knack for finding the best ramen.

SK: One of the things I really enjoyed about making the bomb with Eric, is how creatively aligned we are. When I first approached him about the idea of surrounding the audience with the film playing on massive screens all around them, his immediate reaction was “that’s fucking brilliant.” As it expanded from there to the making of the film with Kevin Ford, the artistic direction with Stanley Donwood and animation with The Kingdom of Ludd, the installation design with United Visual Artists (UVA) and the music with The Acid — we had this consistent alignment creatively.

What was the creative process by which the bomb was created? How did it differ from making a more traditional documentary?

ES: It was truly a collaborative effort. Although Smriti and I are credited as being co-creators, we welcomed and encouraged everyone involved to share their ideas about every aspect of the production. Kevin Ford, Stanley Donwood, United Visual Artists (UVA), The Acid, The Kingdom of Ludd, they all created the bomb with us. This was a group effort. Everyone cared passionately about the piece, everyone had something interesting and useful to say. Nobody signed onto it to get rich, which is good because they would have been bitterly disappointed.

SK: I often think of the bomb as a sculpture or choreography, with various layers that each collaborator added to. It’s quite risky to do something like this in this manner, but we had a lot of trust and integrity. Each of the collaborators had a connection to the issue, an admiration for each other’s work and above all, we would like less nuclear weapons existing in the world.

When did you bring the band The Acid onto the project, and what about them, in particular, spoke to the themes and content in the bomb?

SK: About 10 years ago, a good friend of mine invited me to my first Adam Freeland show (a DJ set) in a three-story Los Angeles venue. He introduced me to Adam, and I have particularly vivid memories of meeting Adam’s mom who was visiting from England and also at the show.

About a year ago the same friend and I were talking about the bomb and playing through some of the music references that Eric and I would often discuss. He recommended that I listen to The Acid’s “Liminal” album which had just been released, and I had an immediate, visceral connection to it.

Through a powerful underlying simplicity, The Acid propel the listener into an emotional journey. In early creative conversations with Adam, he often spoke of the art of a good DJ set in terms of building and releasing tension and then building again. The Acid are adept at creating space, magnitude, and depth by holding back where others might want to go bigger.

As a filmmaker, before thinking of any scene I often think first of the music that would help convey the emotion. While in the making of the film and the original score, Eric, Kevin and I often discussed with Ry, Adam and Steve how nuclear weapons tapped into different emotions - of adrenaline, of fear, of celebration, of chaos, of sadness, etc… — and how the music would heighten those feelings.

Did you learn anything that surprised you while making the bomb?

ES: I learned that sometimes people at the top of their game in various artistic fields are willing to put aside their egos and work together on something timely and relevant. The spirit of collaboration was wonderful and energizing. It could have been a total nightmare.

SK: The sheer reality of nuclear weapons was shocking. The fact that we have 15,000 of them, how hidden they are, that so many are deployable in an instant. Nuclear weapons at their core are machines specifically designed to indiscriminately obliterate human existence. To erase humanity. That feels insane to me. It simply doesn’t make sense to have them just because the technology exists. Once you know this reality, you can’t turn off the impulse to take action.

What is your favorite part of the bomb, whether it be a particular scene or an experience that you had creating it?

ES: I love the insane boldness of it. I remember when Smriti first suggested the basic idea to me, about a year-and-a-half ago. It sounded terrific--and it seemed so unlikely that we could pull it off. Film, animation, lighting effects, a massive installation, thirty-foot-high screens encircling the audience, a great band playing live in the middle of the audience, a subject that could not be more important. Part of me still can't believe we've made it happen. I hope people find it powerful and memorable. But regardless of the critical response, I feel proud of the collaborative spirit in which it was created.

SK: I really enjoyed the collaborative spirit of it. And knowing that each individual artist would elevate this thought-provoking, visceral and multi-sensory encounter with nuclear weapons. Particularly, how UVA’s installation design will bring it to life as a live experience with materials and light. It could be quite shocking, and we’re all looking forward to being inside of the bomb for the first time along everyone else.

Did the experience of making the bomb change your opinions at all about the issues at hand?

ES: I’ve been immersed in these issues for almost nine years now, and making the bomb just reinforced my sense of urgency about the whole subject. People really need to open their eyes, and we hope our work will help them do it.

SK: While getting deeper into the subject it became evident to me that my generation is living under this most awful nuclear threat. There’s an ignorance and amnesia around these weapons existence.

One evening in London, the bomb’s artistic director, Stanley Donwood and I went around asking strangers at pubs how many nuclear weapons they think we have in the world. And we heard a variety of answers - from “none” to “14?” to “335”. Almost no one knew we have over 15,000 in the world. Nor do they know that these weapons are housed all across our countries. What’s even scarier is that the entire system is aging. Which makes the weapons even more susceptible to acts of terrorism. Once you know that, you can’t turn it off.

It really makes no sense to have them, the human race cannot coexist with nuclear weapons. Once you understand how awful the nuclear threat is, it creates an immediate emotional reaction, that present the weapons itself as a universal common enemy.

You’ve got an infinite budget and all the time you need, what kind of project do you tackle?

ES: I would take that infinite budget and start handing it out to all my friends who are filmmakers and musicians, who are struggling to create work that's authentic amid a mass culture dominated by fake, plastic, soulless, corporate-controlled garbage.

SK: I’m enlivened with how storytelling mediums are evolving and increasingly seeing the potential of disciplines integrating with one another. I’m excited about making more films, music experiences, installations, and projects that make people feel aware and alive. I’m drawn to projects that make the invisible, visible.

What are your plans for the bomb going forward? Do you think you will collaborate again?

ES: I hope the bomb will be performed not only in other American cities but overseas as well. Perhaps some day it could also be a permanent installation at a museum or cultural center somewhere. As for working with Smriti again, I'd do it in the blink of an eye. But I think she needs to take a break from the kind of dark subjects that I explore. I hope her next gig is a multimedia piece about the best places to surf in Polynesia.

During the past year, Smriti has waded through more nuclear weapon footage than any human being on earth, except maybe our co-director, Kevin Ford.

SK: the bomb was created so it would travel from city to city. We’re exploring taking it to San Francisco, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Berlin, and Sydney. It can live as both a live event or a long running installation at museums and institutions. We’re also exploring a virtual reality extension and in discussion with traditional distribution outlets for online streaming.

When you collaborate with someone on a project like this, you develop this unique, unspoken language. There is an immense amount of trust and integrity that we have towards one another, the other collaborators and how we portray the issue. It would be an honor to collaborate with Eric again and I really enjoyed how creatively in sync we are. It’s a rare thing to find, and I cherish it greatly.

Lastly, what’s next for you?

ES: My next book is about the American prison system.

SK: Directing more films and multi-media projects. I am not tied to just one medium. I’m writing a science fiction/film noir script, and I have this obsession with getting to outer space. I want the bomb to travel and for everyone to experience it.