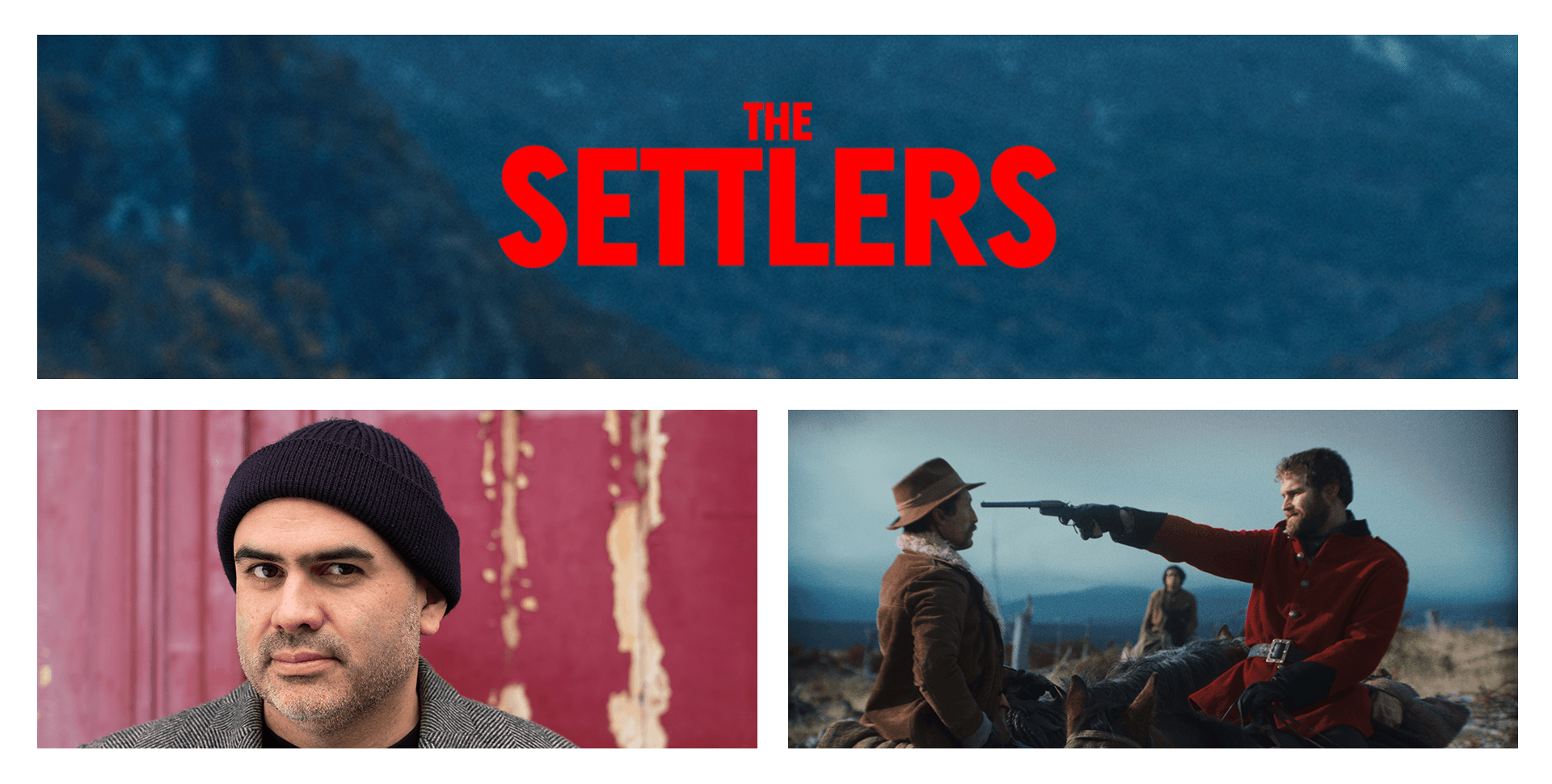

The story of territorial expansion on film has always been one of glory and heroism. Featured prominently in countless Westerns, its depiction tends to lack the real violence and depravity inherent in this takeover. In The Settlers, director Felipe Gálvez Haberle gives a much more sobering and harrowing account of what that kind of colonization really means. Set in the early 20th century in Chile, the film follows three horsemen hired by José Menéndez, a wealthy landowner, to mark out the perimeter of his vast land in Patagonia. Along the way, they meet other men who have tried and failed to rule over the land and the natives who have nearly been run off of their land. Felipe Gálvez Haberle sat down with Borrowing Tape to talk about the future of the Western, historical revisionism, and Chilean cinema. The Settlers is now showing in UK and Ireland cinemas.

[This interview was conducted with an interpreter and transcribed]

Okay, well, I'm Sofia Sheehan of Borrowing Tape, and I'm here today with Felipe Gálvez Haberle, the director of the haunting western, The Settlers. Congratulations on your movie, by the way. And the first question I wanna ask is about the title. Now, the word settlers is a much less divisive, seemingly less violent word than maybe colonizers, something like that. Was this a conscious misdirection?

So I wasn't trying to sort of go for a strong term with the use of that word. Rather my focus was on making it a plural. So, it's a choral film, so I didn't want to focus on there being one type of settler or whatever you ought to call them. But the fact that there could be many, that was a focus.

And the film has such a beautiful landscape. It uses it so well. Where was it filmed and how long was the principal photography?

It was filmed in the Tierra del Fuego, on an island and the filming took four weeks.

Making a Western in this day and age, it feels like you have to change a lot from the original genre. How did you go about adapting a Western from an even more modern, subversive audience?

So rather than being about adapting or changing the style of the genre, what I wanted to do was to focus more on the kind of pages that have been torn or erased from history. So it was about filming those scenes that might be censored or excluded from a traditional Western. First and foremost, I was seeking to create a classic. I wanted there to be iconic scenes. It's a film that's very kind of self-aware, cinephilic. So I wanted that to be many references in there to other films. Includes references to dialogue in other films, to choice of clothing, outfit, actions, and scenes from other films. And it's a film that's always in dialogue with other Westerns and with other war films.

Now, you've had a lot of experience in the film industry, mainly as an editor. What made you decide to direct and how is this experience different from your first solo feature film?

So yeah, it was, I'd always wanted to be a director, especially, especially a film director, but that's a difficult path to pursue. It was really hard making it as director and this is my first film. But before that, I was an editor. I had lots of experience being an editor and that's where I felt comfortable because I'm quite a hermetic solitary nature kind of guy. I don't like the crowds you get on set. I prefer to be as you are as a director as an editor, you're just alone with the director. I'm much more comfortable there. And so, this experience as editor also enabled me to learn a lot about filmmaking, you know, what others did well, what others did badly, I could learn from their mistakes, what went well. I could also learn about what went well in terms of the script. So I use that experience, I leverage that experience in filming this. So, when filming the sets, we managed to do them in really few takes. No scenes in the film actually took more than three takes. I'm also really selective when filming scenes as well. So when I saw that something wasn't working, we tried it once or twice and it wasn't working. I just jacked it in and we created a new scene. I never stick with something that's not working. It's my belief. And all of this experience kind of enabled me to improvise as well. There was actually just one scene in the whole film that didn't get included.

And then of course there's also the scene with, MacLenna shouting at Segundo. And this was an improvised scene. So that ability to improvise and come up with things on the spot because I knew I needed some arguments and some tension between the two of them. So, yeah, I went into this knowing what I needed. This is my first step as a director and I hope to continue.

Are there any directors and films that inspired The Settlers?

Yeah, so I see it as kind of like a game. It's enjoyable to play with that. It's absolutely jam-packed with references. Some scenes have five references in them, different ones, and some of them are more well-known than others. But I wouldn't want to reveal to you which they are. You could ask me and I might tell you I might not.

Will do a bingo later and see if I can guess. Are there any themes and subject matters that you see as really interesting to explore as a filmmaker and through lines you wanna continue?

Yeah, so what I like to explore is the different genres, more than through lines. So Western is obviously an important genre, kind of propagandist genre, although it's not the only one. So yeah, I like to study all these different genres and think about perhaps in the future making films using some of these other genres, not Westerns. Perhaps some other genres that are propagandist in nature that have been throughout history. And kind of going into those genres to kind of deconstruct them from the inside. So using their own rules and their own formats to deconstruct them from within. In terms of Westerns, if you think about revisionist Westerns, what they tend to do is they tend to change the behavior of the characters. And what I want to do rather than change the behavior is change the discourse itself.

It's interesting that you bring up propaganda because, at the end of the film, there's a scene where a government official uses film to create this, to further this false narrative and it kind of suggests a complicity not just with the government but with you know all fields arts of creating this — was this intentional?

Yeah, I think that film has definitely been kind of complicit in the genocides of the indigenous peoples in the 19th and 20th centuries. When I wanted to make Los Colores with The Settlers, I didn't want to kind of put myself in this position of moral superiority and saying, oh, look, I'm better than other people. I wanted to say rather, we're all doing this to kind of take a self-critical stance and see how filmmakers, photographers, everyone in this industry is also complicit in terms of how we've taken part in colonization. We've been involved in producing propaganda, in sort of promoting this idea that the killing of indigenous people is a factor that promotes civilization and increases the civilizedness of the world. And then we've also produced entertainment. We've developed these stories that show the Indians as the baddies and the settlers as the goodies. So I think it's important to question cinema, question film, and it's the capacity it has to rewrite history because he who holds the camera also holds the pen. In terms of, they write the narrative, they say what happened.

Last question, what do you want audiences to take away from this film when the credits roll?

Yeah, so for me, reflections, doubts, questions. For me, the film wasn't trying to, I'm not trying to be a judge or an arbiter, nor am I trying to be a historian. I don't want to be that. I don't want to be either of those things. What I want to be is a film director and I set out to provoke not in the sense of provoking just for the sake of it, just to get a reaction, but in provoking, stirring up the audience so that they have questions and doubts and reflections. I want people to, go away from this film and talk about the film and the doubts that it might have raised for them. Because people could very well go away and defend Jose Menendez. They could say it could justify what he did. They could say that's the price you have to pay if this is what you want. So I think what I want is, I want to leave the audience to decide with whom they want to empathize rather than telling them. I want to leave open questions.