It is often said that those who view the world in black-and-white have trouble seeing the whole picture, and this goes to show for the streaks of red covering our television screens. Consumer culture runs rampant with the notion that to have is to hoard and to collect is to control. But what does the pursuit of satisfying these desires say about the primal urge for power, and to what degree do humans’ violent tendencies have to show for it? These ideas are explored in Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor’s 2009 science fiction film Gamer. While glazed over with gratuitous amounts of gore, brutality, and overt sexuality, Gamer’s surface-level thrills house a time capsule—a message from the past that is even more relevant now than it was over ten years ago when the movie was released. In this evolving age of technology, government oppression, and civil uprisings, the video game-inspired action flick is a reflection of the fear that currently plagues society today.

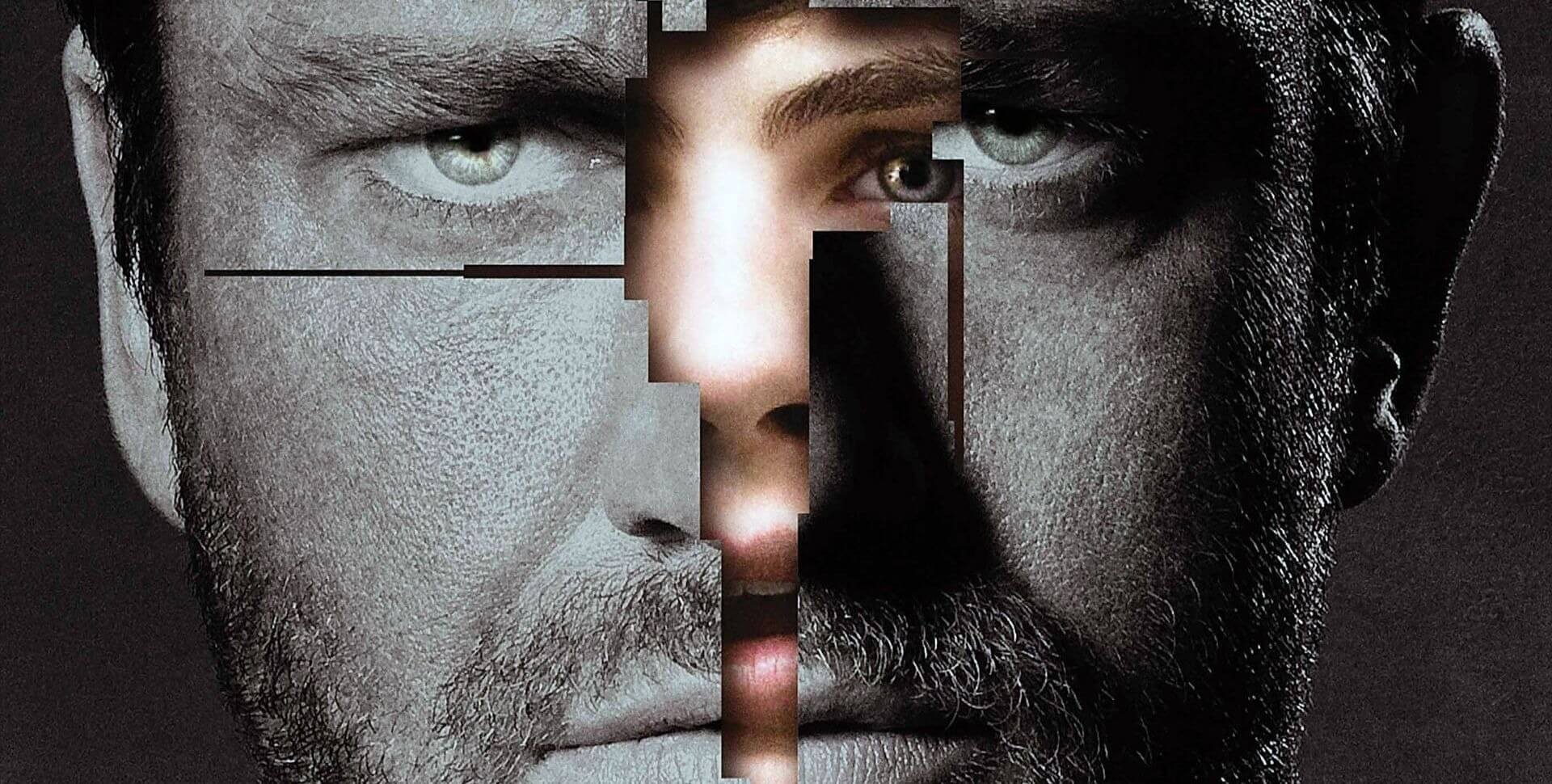

Taking place in the not-so-distant year of 2034, Gamer’s plot is set in a world where state-of-the-art gameplay has reached frighteningly immersive levels of entertainment. Computer programmer Ken Castle [Michael C. Hall] creates nanite technology to replace brain tissue that enables humans to control others and see through their perspectives. This technology is applied in a real-life virtual simulation game, Society, where players can control the actions of other people willingly participating as avatars. Another game that Castle creates is Slayers, a first-person shooter that uses death row inmates as the playable characters using weapons in a deadly sport. While the people who act as playable characters in Society get paid, the inmates being used as avatars in Slayers are playing for a chance to get released from prison—if they can survive 30 matches, which is a feat that no person has come close to accomplishing except the protagonist of the film, John “Kable” Tillman [Gerard Butler].

Society

Slayers

Angie (Amber Valletta)

Kable (Gerard Butler)

Once the rules of this universe are established and understood by the viewers, Gamer proceeds to depict an alternative civilization where citizens are desensitized to a startling degree by the level of vulgarity and violence exhibited not only in their virtual lives but in their everyday existence as well. This acts as a commentary towards a corrupted American dream, based on a society where it is heavily suggested that the same technology used to entertain them will one day have the capability to control the populace against their will. In a post-9/11 world rife with fear surrounding leaders abusing their power and recent pandemic paranoias, Gamer unearths the vulnerability we have felt as a nation for quite some time.

We are consumers in that we seek a sense of pleasure in the pain we bring upon others and ourselves. The characters in the film thrive off selfish motives, whether it be to relieve a sense of sexual perversion by taking control of Society actors or finding primal satisfaction in watching fellow men kill themselves for a chance at the freedom they never really possessed in the first place. Kable is the placeholder in which viewers of the film can insert themselves, as his intentions are not fueled by self-gratification, but the wholesome wish to reunite with his wife and daughter, both of whom have been prisoners in this virtually vicious cycle in their own way as well (Kable’s wife Angie, is a Society actor (Amber Valletta) subjected to heinous acts and his daughter has been put in the custody of a different family).

As opposed to other films heavily influenced and centered around video games, Gamer does not rely on cheap gimmicks or cliches of the concept to drive its point across. Devoid of the colorful logos and familiar trademarked characters of the pop culture-infused Ready Player One, Gamer relies on the grit of the human condition, with its first-person shooter aspect only assisting in elevating these themes rather than using it just for the novelty. If any thematic comparisons could be made regarding this film, the use of hyper-violence to demonstrate the disturbing tendencies of man is very reminiscent of the coined “ultraviolence” from the controversial dystopian Kubrick film, A Clockwork Orange (1971). Here, societal control is justified through the extreme levels of the brutality depicted by its characters and is used as a means to tame these beastly urges to form a more proper, model citizen. In the case of Gamer, violence is a necessity for a world that is being crafted in the hands of manipulators and power-hungry abusers. The excessiveness of bloodshed and promiscuity is not overkill, as these are the attributes of a society derailed by the normal standards of living that have long been abandoned.

Gamer was released with a poor reception at the box office and received many negative reviews, mostly focusing on the content of its hard R rating and writing it off as another testosterone-laced gun show that held no significance in the procession of other blockbusters scheduled to be out that year. It was the consensus that using violence to protest violence was the downfall of the picture, but as history and recent events have demonstrated, is it not a repeating trademark of our culture? Gamer exemplifies the purpose of the science fiction genre—in that through a seemingly impossible scenario, we as a people find the flaws of our making and the truth we so desperately want to uncover as a mirrored counterpart to our own reality. And just as this film displays the dramatized and intentionally exaggerated faults in contemporary society, there is a feeling of escapism. This escape is anything but a release. It is not to a place of what could be, but what already is, prophesied and interpreted through the projected images on a broken screen.