Ghosts of War follows the story of five American soldiers who are assigned to take refuge in a French Chateau during World War II when they discover a brand new enemy in the form of a supernatural force. Written and directed by Eric Bress (The Butterfly Effect), the horror/psychological thriller film stars Brenton Thwaites (Oculus), Kyle Gallner, Theo Rossi, Skylar Astin, and Alan Ritchson.

Recently, Eric Bress gave us an in-depth interview on the many facets of the filmmaking process for the feature film, Ghosts of War - from writing the screenplay, casting, cinematography, editing, and on-location filming. We also find out the filmmakers/directors he admires and his advice for budding filmmakers. Ghosts of War is now available to watch via Virtual Cinema Screenings, On Demand, and Digital.

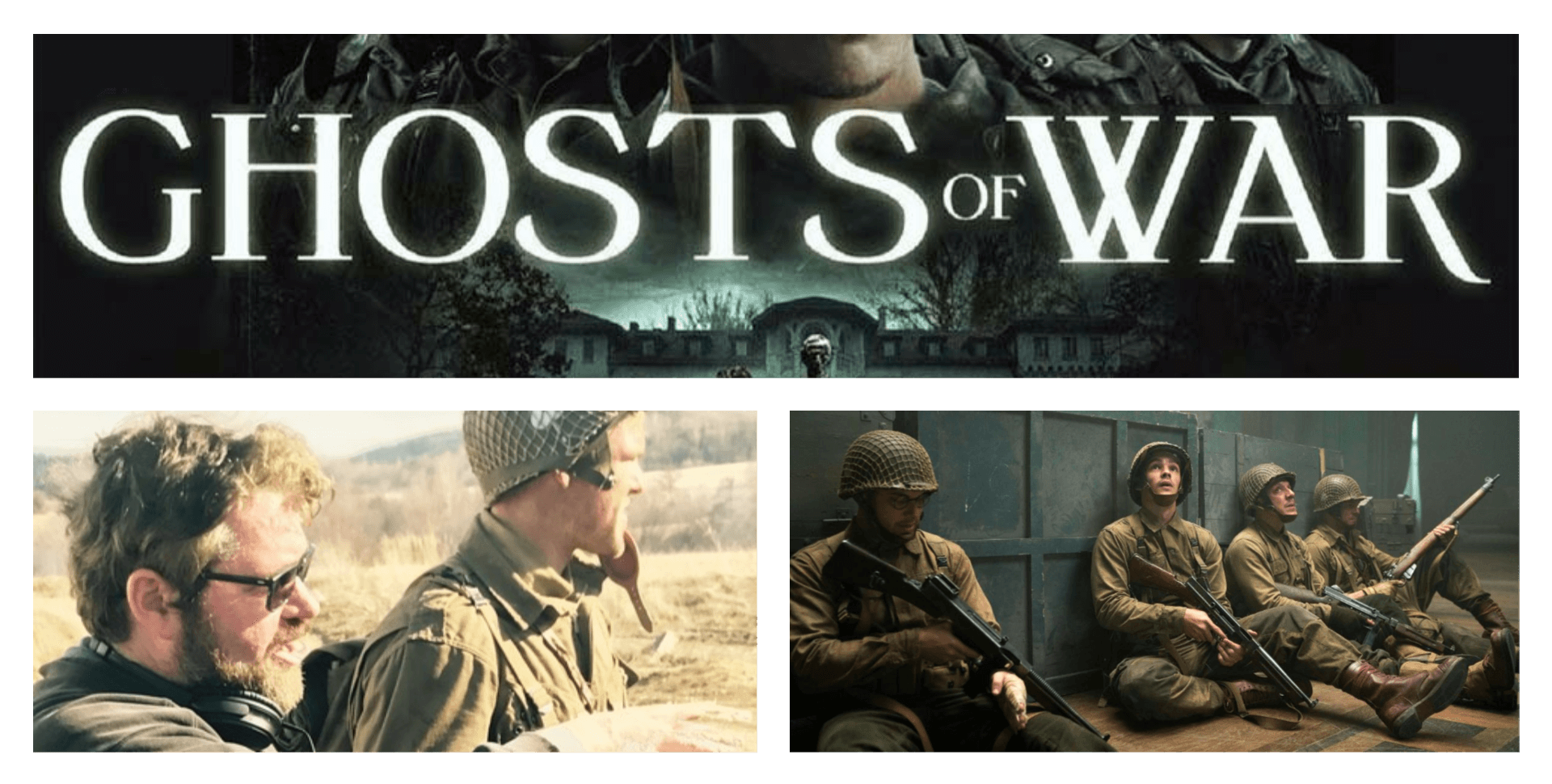

Photos courtesy of Vertical Entertainment

'Ghosts of War' features a very talented ensemble, and Kyle Gallner as Tappert is just phenomenal. How did you go about the casting process?

Brandon Henry Rodriguez is an amazing casting director, and we became friends throughout the process, (since finishing the film, we take trips to the shooting range, though that’s not important right now). He worked tirelessly within our modest budget to get this amazing cast together. I watch a lot of movies and have a fair understanding of whom most of the actors are out there, but a casting director has a unique gift that is all-too-undervalued. I’ve worked with producers that want to cast the entire film themselves and I always push back because, in my experience, a great casting director will bring ideas to the table that you’d never have thought of. They know not only the top 2000 actors on the IMDb STARmeter, but thousands more who are up and coming and might not get investors excited but will be the best fit for the film. For Ghosts of War, I was able to have my cake and eat it. Even though we didn’t have a ton of money to throw out there, Brandon was able to get the script to some high pedigree actors that I’d known and loved for years but had doubts that their reps would let them do a genre picture. Still, casting was a bit of a mad scramble because I was already in Bulgaria doing pre-production and most of the parts hadn’t been filled yet. Kyle Gallner was actually the last actor hired for the ensemble. He was amazing in his role and crushed the audition. The only problem was that he was contractually obligated to keep his hair shoulder-length for a tv show, and could not, would not, cut it for the film. We both agonized over what to do, then Kyle found some photos on the Net of World War 2 of snipers who were given certain leniency with the dress code and allowed to wear knit caps while perched in their nests. Knit caps… which would cover all that long hair. It actually worked better in the film to have his character wearing a hat. Sometimes, in war movies, when you first introduce a bunch of soldiers whose faces are all caked in mud and they’re all dressed alike, it’s hard to tell them apart. Any opportunity to visually distinguish my characters was one I wanted to take. I loved Brenton Thwaites from Oculus and several other big films, so it was lucky that I was able to cast him in the lead role. He has this amazing quiet-cool screen presence, like Steve McQueen. A natural leader who doesn’t have to speak to make his intentions known. What really helped is that he had just switched over to United Talent Agency, which was also my agency, and that helped grease the wheels a bit. He was my top pick, and if he were at any other agency it would have been impossible to get him.

Ghosts of War offers a handful of major twists. How did you plan to write for those moments and ensure it provided the most impact on-screen? Can you tell us how you handled the writing process?

Most twists come at the very end of a film, with about 90 seconds to wrap everything up, leaving the audience shocked and amazed by the time the credits land. I knew I wanted a major rug to be pulled with more story to tell afterwards, than I could ever do in 90 seconds. It was really tricky to hit the audience with a bomb and still keep them interested for another 15 minutes. So within those 15 minutes, I had to slowly dole out one revelation after another, to keep the audience from growing fatigued now that they were let in on a big secret. I kept making changes, unsure of how to nail it. I was even sending new drafts of the last pages to the producers while we were nearing the end of shooting, shuffling up the order of things, cutting back and forth from different locations, creating flashbacks of what was originally going to be chronological, trying different things until it all finally made sense to me how to achieve what I was going for. Even then, once you’re in the editing room and have the luxury of restoring things to a more linear, chronological narrative, we played with different options, making sure we weren’t missing some other opportunity to make it even better. Ultimately we went with the final version of the script, cutting a few lines of dialog out of the film where we felt it might be dragging as we raced toward the finish line.

How did you find the role of directing 'Ghosts of War'? Could you describe some of your favorite and most challenging scenes while filming? Specifically, how was filming the harrowing PTSD memory scene, where the brutal murder of the Afghan family happens?

The Afghan family sequence was far and away the hardest part of the shoot. It came at the tail end of the production when I was exhausted from shooting six-day weeks. Up until then, almost every scene was storyboarded and laid out in detail, mapped out with my DP Lorenzo Senatore, but for some reason, this scene slipped through the cracks. Maybe I thought I could wing it on the day once we had all the actors on the set. But then I’m trying to direct 20 actors and extras that don’t speak English and block the scene so we know where to place the cameras for all the coverage. Easier said than done. It was hot, and my leads were cramped into a small space, everybody getting frustrated. There was one point where I was so punch drunk and frustrated from the inability to communicate with the cast that I nearly walked off the set to cry in private somewhere. That wouldn’t have been a good look, though, so I sucked it up and slowly, inch by inch, managed to work my way through the blocking. We had three days to shoot everything for that part of the movie and we were racing the clock and the setting sun every day. And on the last day, it snowed. Like, blizzard snow. And we’re supposed to be in a hot dry climate. And I saw all the snow falling on my van ride to the set and just began laughing. Because there was nothing I could do about it. By 10:00 am the snow was still falling, but I was rationalizing I could add in a sound effect of an explosion and I might be able to get away with it looking like ashes or something. Between shots, I was running around the outdoor set swiping patches of snow of the set. Ultimately, there are one or two shots in the final film with falling snow in them that, knock wood, people don’t seem to notice.

You previously worked with Composer Michael Suby on 'The Butterfly Effect' score, how did you find working with him time around on 'Ghosts of War'?

Michael Suby is a genius who I’ve had the pleasure to work with not only on The Butterfly Effect, but he also scored “Kyle XY”, a show that J. Mackye Gruber and I created a few years after Butterfly came out. He’s extremely busy and was working on four network shows when I asked him for a huge favor to do this film. It was a big job, because the film crosses genres and dimensions and it all rested on Mike to be the sonic curtains that tied the room together. Melodies and themes used in the “war” section of the film were composed with more traditional orchestration and that were later transposed to synthetic and analog instrumentation as the film moved into horror and beyond. He created sounds from instruments he made out of weird objects and incorporated them into the traditional score. The movie evolves through different layers and Mike had to brilliantly incorporate the changes and make subtle transitions so that all elements of the film would come together, no matter how different they were, based on the shared melodies and themes.

Since you've also worked with Editor Peter Amundson on 'The Butterfly Effect,' did you find that there was an advantage/shorthand working with him again?

Peter is an amazing, diligent, and focused editor and we definitely had a shorthand going into this project. I knew the kinds of transitions he liked so I could incorporate that during shooting and how he liked to edit to keep the on-screen geography consistent. For example, if you watch the film, most cuts between actors and objects share an eyeline, or a “hinge” where we cut from an object to the person staring at it, and when that actor shifts his gaze to another person, it’s a “hinge” that creates the opportunity to cut to the second person returning the look and then following where that person’s eyes go next. You don’t think about these things as a director, but as an editor, they’re essential to creating a fluid language of geography and connection throughout the film. He also knows how to cut action sequences with the best of them, working on big-budget action movies through a great deal of his career, so I could entrust him to best tell the story through the art of editing, knowing which frames he could trim and still keep the audience following the action, or which coverage will best cut to what once he was given all the footage from the scene. We’ve developed a deep friendship over the years and I trust him implicitly when it comes to protecting the vision of the film.

How was it working with Cinematographer Lorenzo Senatore to devise the visual aesthetic for Ghosts of War?

Lorenzo is one of the best Steadicam operators in the business, but even more valuable for establishing the macro-vision of the film as a Director of Photography. He not only works with me, interpreting what I want emotionally from a scene or sequence into the shooting style but then worked with the production designer, Antonello Rubino, to make sure the sets would be built with that aesthetic in mind. His mind never stops working and he always goes for the best way to get the image, using different lenses, filters, technocranes, etc. to translate the story into an emotion. For the first section of the film, we used old-school anamorphic lenses, the kind that Spielberg used in the 1970s and 1980s, then switched to more modern spherical lenses to capture the final act of the film after a major event happens. There was no tool he didn’t use to best enhance the visual art of storytelling, yet did it in a way that is seamless and doesn’t pull you out of the film when you should be concentrating on the story points.

Which films/directors have had the most significant artistic influence on your filmmaking, on your film Ghosts of War, and why?

Stanley Kubrick is by far the director that made the most profound impact on me, which is a cliché thing to say I guess for anyone working in horror. The way he made the Overlook ominous and unsettling and powerful by the way it was shot and edited. There are several homages to The Shining in this. For example, in one scene, the soldiers put white flour all over the floor as a way to track the ghosts’ footsteps, and the scene begins like a shot in The Shining where the door to the Overlook has opened, letting the blizzard outside cover the floor in snow. A more recent director that I’m inspired by is Mike Flanagan who has seemingly perfected the craft as well. The moments of suspense and prolonged tension in Oculus, Doctor Sleep, and The Haunting of Hill House series are fantastic. There’s a next-level artistry in everything he does. There are still episodes of Hill House I haven’t watched because I want to save them and want to be able to look forward to seeing them. After I saw one episode that was a single tracking shot, I was so blown away I decided to stop binging, so I don’t blow through the experience in one sitting.

Best piece of advice you'd share with budding filmmakers?

If they’re “budding”, that means the climb will be a difficult one. I would recommend coloring inside the lines, meaning, playing by the rules of Hollywood and make sure your writing strictly adheres to traditional screenplay structure. I spent years trying to write outside the box and ignore the “formulas” of the typical Hollywood screenplay. I was an idiot. No studio executive will ever be handed a script by a writer who’s decided he’s too cool to play by the rules, no matter how inventive the dialog or how badass the characters are. Show the bosses that you’re willing to play ball and maybe someone will hand you a uniform. And do not expect overnight success. I was willing to spend ten years as a struggling artist before I made my first film. It only took seven luckily. It was the number one film in 17 countries. I figured I was in the club and should be making a film every year after that. But Hollywood has an endless well of dues and I never thought it would take 15 years to make my second film. So unless you decide you simply cannot do anything else but be a filmmaker, for God’s sakes, get that law degree like your dad keeps asking you to! It’s cheaper in the long run. You’ll thank me for it. But if you can’t see any other career for yourself, read the books by all the greats, develop your craft and never stop trying.