With the recent buzz surrounding Parasite, now is a good time to discuss the cultural inspirations and impact of an earlier film, High and Low, that eventually inspired Bong Joon Ho in the making of Parasite. High and Low is a Japanese crime drama directed by Akira Kurosawa in 1963. Kurosawa is most famous for his jidaigeki, or period dramas, like Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, or Rashomon featuring samurais and their own stories. He has always used his films as commentary of the world around him, and High and Low is perhaps his loudest commentary on post-war Japanese society.

The film revolves around Kingo Gondo, a wealthy executive for National Shoes. Gondo is presented with a moral dilemma where he initially agrees to pay a ransom for his kidnapped son, but he finds out soon after that it was actually the son of his chauffeur. Despite this, the kidnapper still demands a ransom no matter whose son it is. To add another dimension to this predicament, Gondo just took out a mortgage on his home, which looks over the poorer population of Yokohama, to buy a controlling share of his company. Gondo is forced to ask himself, “Should I pay for the life of someone else’s son if it causes me financial ruin?”, he maneuvers this dilemma with the help of his wife, assistant, chauffeur, and the police. Inspired by the book King’s Ransom by Evan Hunter under the pseudonym Ed McBain, this rendition takes its liberties by extending the story far beyond its original conclusion and turning it from a pulp crime novel to a critique of certain aspects of Japanese society at the time from an increase of kidnappings, class division, to the westernization of the country.

One of the most obvious connections between this film and post-war Japan is the kidnapping. Kurosawa was inspired by the increase of ransom kidnappings that were on the rise due to the growing prosperity of post-war Japan. The laws about kidnapping for ransom were relaxed at the time, classifying it as robbery, and there was growing demand to revise them. There were 13 cases of kidnappings for ransom that were prosecuted in the five years leading up the movie compared to only 2 cases just a decade earlier. In 1964, the law changed kidnapping for ransom from a crime carrying a 1-10 year sentence to carrying a life sentence.

The kidnapping case most closely associated with High and Low was the kidnapping and murder of Yoshinobu Murakoshi, who was abducted just 30 days after the release of the film. The kidnapper admitted to watching the film just 11 days before the abduction happened, but did not comment on whether his actions were inspired by the film. Others wanted to copy the events in the movie and made phone calls threatening to kidnap Kurosawa’s family members for money.

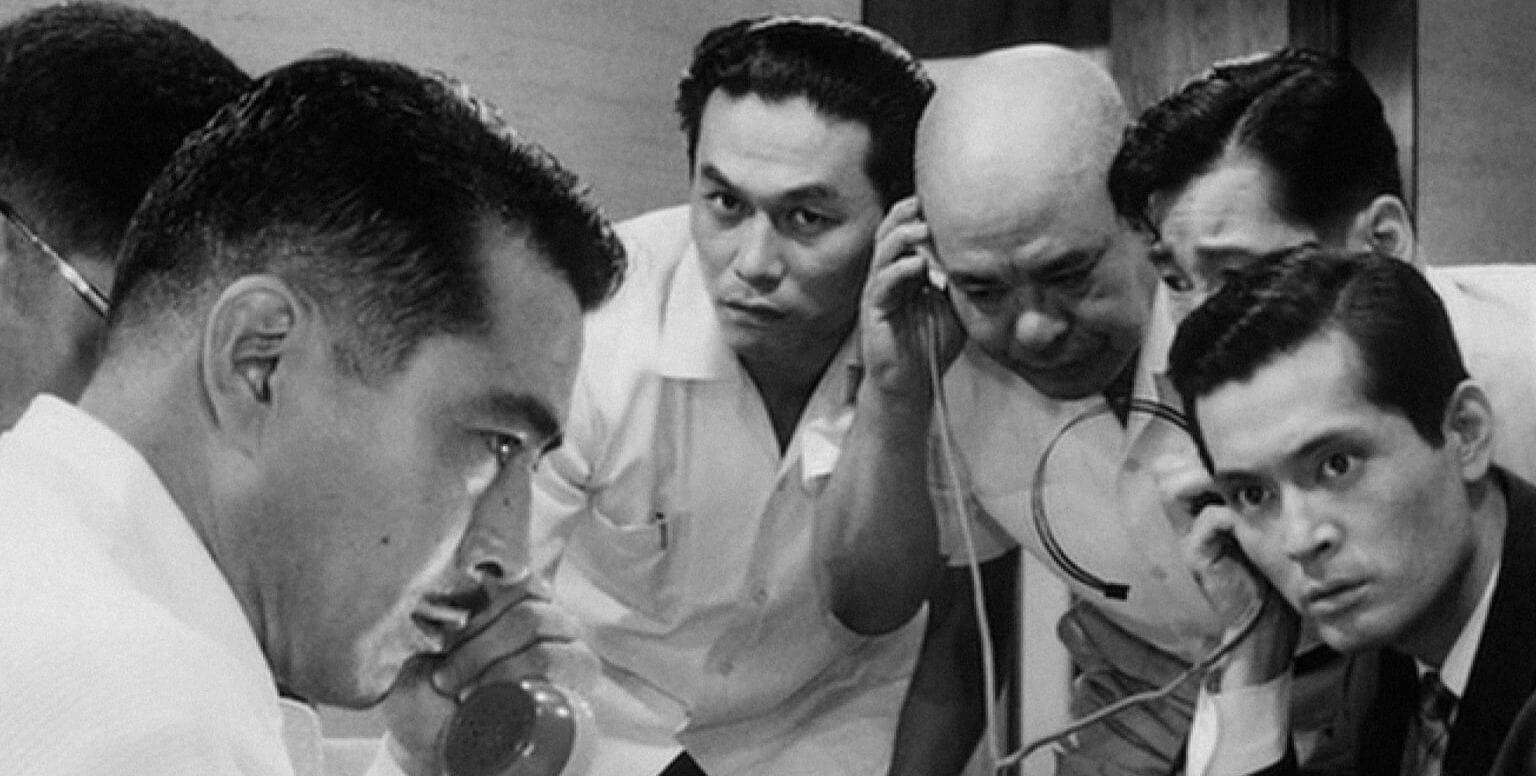

Kurosawa was a reformed Marxist who still stayed on the left of the political spectrum - in terms of class division, and such beliefs are reflected throughout most of his work. High and Low is considered his most political film due to its modern setting, especially in its commentary on class division. The High in the title refers, among many things, to the rising middle class that emerged from post-war Japan, and the Low referring to its counterpart, the increasingly desperate poor population. Nothing is more exemplary of this class divide than Kurosawa’s use of heat in the film. Kingo Gondo’s house, which overlooks all of Yokohama, has air-conditioning; a new commodity for Japan in the 1960s, which was usually reserved for the wealthy. The contrast to this is littered throughout the second half of the film where everyone has sweat-soaked shirts and desk fans on blast. In a telling final scene of dialogue between Gondo and the kidnapper, Takeuchi, he emphasizes this by stating that it was “so hot in summer [he] couldn’t sleep.”

Note the table fans and the sweat that soaks the investigators shirts.

Gondo’s house that looks over Yokohama.

Money wasn’t the motivation for Takeuchi especially considering that he was a medical intern and was ensured a nice salary in the future. Takeuchi felt taunted by Gondo’s large house that loomed over the slums of Yokohama, and resentment grew within him every time he saw the closed curtains on that house; an obvious sign that his house was air-conditioned. Takeuchi didn’t act out of the desire for wealth rather he acted out of hate for someone who, intentionally or not, flaunted his wealth with a “house that looked like heaven” to the lower classes. The police detectives even agree with this noting that the “house gets on your nerves.”

Gondo in many ways represents the westernization that was happening in Japan during the occupation by the United States after World War II. His house replaces the features of a typical Japanese home with modern furniture and a pendulum clock that chimes the tune of Big Ben. The only thing that ties the movie to Japan in the first hour of the film, other than the characters speaking Japanese, is Gondo’s wife, Reiko, who wears very traditional clothing. The chauffeur’s and Gondo’s sons play cops and robbers, an American import which is a call back to the original King’s Ransom source material.

Note the western décor.

Post-war Japan was a very transformative time for the country. The United States occupied the country after World War II and Douglas MacArthur was appointed as the SCAP (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) to supervise the occupation. The Americans had an opportunity to control the direction of the culture in Japan, and with the threat of communism growing bigger in the East, they used this opportunity to make Japan an America-friendly nation. Many Japanese citizens, fatigued from the war and attracted by the freedom and material abundance of American culture as presented by their occupiers, started to “Americanize” themselves in the process.

Kurosawa is considered to be the most western director to come from Japan. By the influence of his father, Isamu Kurosawa, he was exposed to western art from an early age. He has received criticism for pandering to the West, though he has defended his use of mambo music in Seven Samurai by saying that “If purely Japanese music had been used I don't think the young people would have felt what that character was like, how much he resembled them… Oh, I'm Japanese all right. I'm truly Japanese.”

As for the connections between High and Low and Parasite, there are two very strong ones. The most obvious one is the use of height to represent wealth and status in society, with the Gondo and the Park family living high up on in the hills while Takeuchi and the Kim family live below. Class division is a strong theme between the two films. And I am sure that the theme of smell to represent the poor in Parasite comes directly from High and Low when some police officers cover their noses as they find the kidnapper’s accomplices overdosed on pure heroin.

The parallels of smell between the two films.

The final scene comes right out of the Dostoevsky playbook. It tries to understand the kidnapper, rather than praising or condemning him outright. It is a simple, humanist scene where Takeuchi is to be executed soon and he requests to see Gondo one before that happens. Gondo isn’t exactly mad at the kidnapper, but accepting of the hardships of the past and moving forward in his life, much like the Japanese population after the war. This scene provides no real answers but is like a calling to you to accept the past and to do the best for your future. The final scene of the movie leaves the viewer exactly how it leaves Gondo, sitting in self-reflection.

Gondo sitting in self reflection for the last shot of the film.

Watch High and Low via Amazon