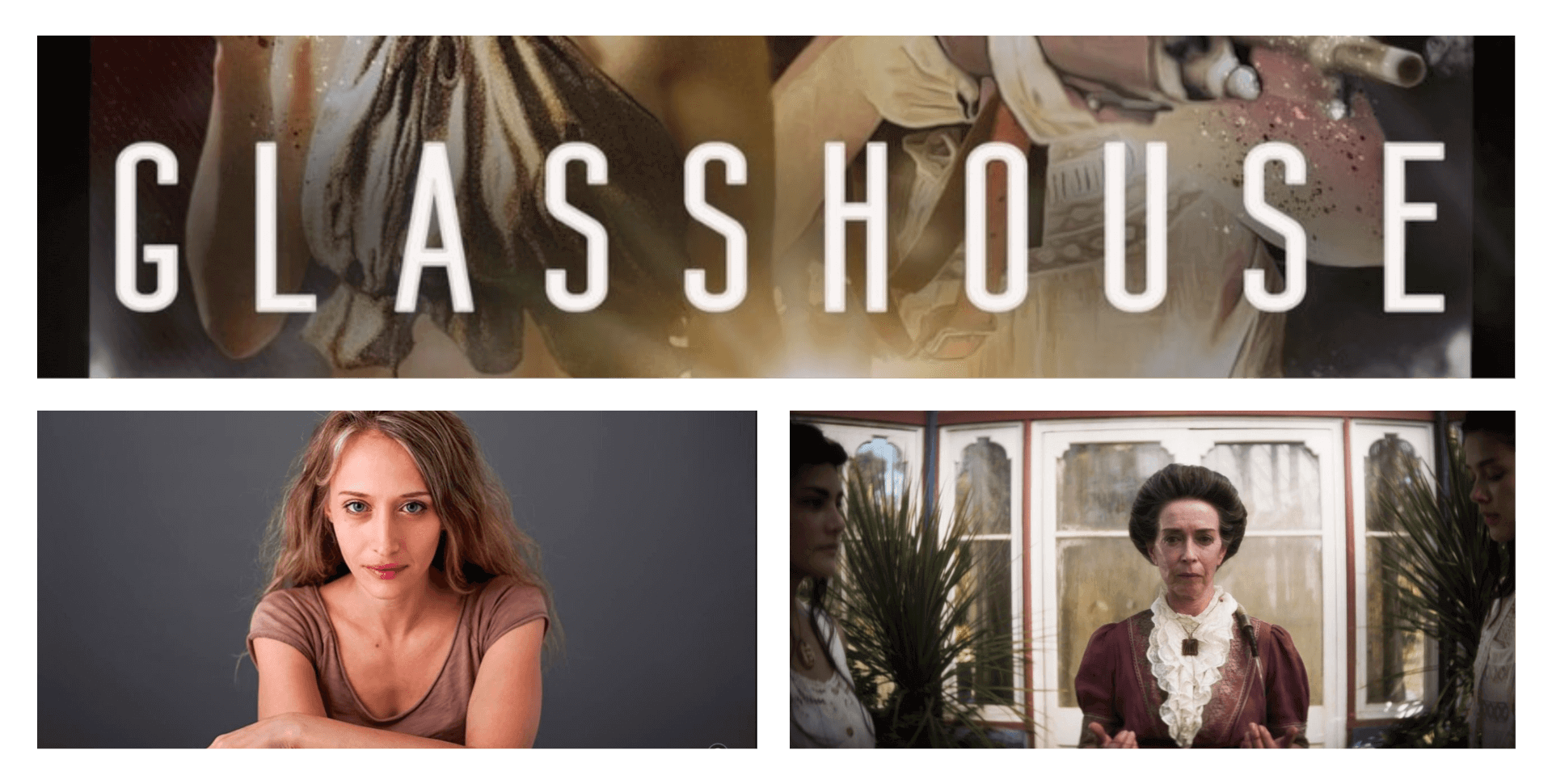

Glasshouse is a drama | sci-fi | thriller film that follows a family surviving 'The Shred' — a memory-erasing toxin in their air by living confined in a glasshouse. Kelsey Egan directed the film and also co-wrote it with Emma Lungiswa De Wet.

Borrowing Tape scored an interview with the Glasshouse filmmaker Kelsey Egan — as part of our Fantasia International Film Festival (2021) coverage.

Glasshouse premiered at the 2021 Fantasia International Film Festival.

What was the inspiration for Glasshouse?

A tangle of influences and ideas. The core inspiration for me was an interest in exploring the impact of memory on behavior and identity. Memories mold one’s sense of self and perceptions of the world. Who we are is informed by our experiences. The past shapes us, and our memories color the present. Relationships gain meaning and significance from shared history. We are who we are because of what we’ve done and who we’ve been with. Sometimes, things happen that change us… and these changes aren’t necessarily for the better. Are all memories worth keeping? Glasshouse explores two opposing coping mechanisms to trauma: holding tightly to the past as a form of preservation, and willful forgetting.

What was the casting process like for Glasshouse?

To maximize our outreach with health and social distancing in mind, we received all our auditions as self-tapes. The casting process was quite rigorous as we received hundreds of tapes and spent days watching them. For Bee and Evie, for example, we received over 120 tapes each. There were so many exceptional performances — we wished we had more roles to cast. But in the end, Anya and Jess most effectively captured the essence and divergent energies we were seeking for the characters.

Glasshouse explores things like incest, using dead bodies for fertilizer and rituals, and intentionally harming oneself to forget bad memories. How did you find it collaborating with screenwriter Emma Lungiswa De Wet for Glasshouse?

Emma is a treasure. She’s my work wife and an exceptional partner. We met in 2016 when we were selected to participate in one of the National Film and Video Foundation’s writing programs, and quickly discovered we shared a mutual affinity for all sorts of crucial life things, like gothic literature and grammar and work ethic and tea. We subsequently wrote together on a series and became better friends. I knew I wanted to work with her more and had been hoping that the right opportunity would come along. Brainstorming concepts for this slate was the beginning, and I couldn’t have hoped for a more supportive, creatively united collaboration. It was the fulfillment of a mutual dream, and I’m so grateful that we’ve been able to go on this journey together.

Technologically speaking — what year is the movie set, and when does The Shred take effect?

We intentionally didn’t choose a year. In many ways, this film is a meeting of past and future, unrooted in time or place. It could be anywhere. Perception of time and even geography changes when one is suddenly cut off from the world – time passes in a different way. It could be 30 years in the future. It could be 100.

Near the end of the film, Gabe digs up a burial with necklaces that resemble his sister's ones — E and B. The voiceover states: "Our faces may change, but our names do not." Could you tell us more about this revelation and the ending?

The crux of this ending is the reveal that the Evie and Bee we know are not the original Bee and Evie at all. The implication being that all members of the family have been replaced, innumerable times, and have simply forgotten their actual origins. Since memory is unreliable or non-existent, whatever family narrative is adopted becomes the reality, or accepted history, of the family in that given iteration. In this way, the stories they tell and rituals they follow are truly necessary to maintain their sense of identity – without this narrative, they would have no context or sense of identity. In reciting, or remembering this narrative – they define themselves and their relationship to one another. It’s as Evie proclaims when she takes Mother’s place: “Those who remember remain.”

Can you tell us about the creative choices behind the production and costume design in Glasshouse?

The costume design was informed by both aesthetics and function, and the production design focused on the practicalities of transforming a greenhouse into a home. Our production designer, Kerry von Lillienfeld, is a genius – in a matter of days he brought the vision of Glasshouse to life.

Pearson Conservatory – where we shot Glasshouse – is an astonishing location. The greenhouse was transplanted from England and erected in 1882. It’s essentially a relic of colonialism in the midst of the oldest park in Gqeberha, previously known as Port Elizabeth.

Just as the film is a fusion of genres, our approach to the design was a fusion of influences and periods. Practically, the glasshouse was hot. If I lived in a humid greenhouse, I’d want to wear as little as possible. And it’s not like this family has any concerns about modesty – there’s no reason to. So it made sense that they wear loose-fitting, billowing, comfortable clothing with a nod towards Victorian influences due to the symbolism evoked by such dress. Costume designer Catherine McIntosh brings such exceptional attention to detail; she did an exquisite job interweaving period elements into the looks she designed, with an eye to creating practical, breathable costumes that captured our characters’ unique personalities. All this on a shoestring budget.

Victorian-era dress carries such heavy connotations. Historically, colonial settlers have inserted themselves into new geographies and behaved as though their way of life is “more correct” than any other. Their ideals and belief systems were forced on other cultures. Similarly, the Victorian dress is symbolic of traditional Western ideals for femininity and gender stereotypes, often physically manipulating and molding women’s bodies to fit into these ideals. But this dress is designed to maintain an illusion. It does not reflect the truth of the flesh and blood beneath. Similarly, the Glasshouse is also a mirage. Much like colonialism, its idyllic façade is a mask for the rot beneath. There is a price for this sanctuary. A price paid in blood. Our family’s narrative is a fragile one. Their truth is tenuous.

Our female characters have no sense of societal taboos or gender stereotypes. As a result, their behavior is quite pure – honest and raw. The sense of confinement evoked by Victorian costumes and bonnets is a tangible, visual representation of the confinement the characters experience as a result of the Shred. They are trapped by the conditions of their world, but it is an environmental threat rather than a societal one. Their behavior and impulses are pure and unbridled – this dynamic contrast between image and reality in the film’s design provided a visual metaphor for the themes explored in the film.

Where did you film, Glasshouse?

We filmed at Pearson Conservatory in St. George’s Park, the oldest park in Gqeberha (a city in South Africa).

What was it like working with Composer Patrick Cannell on the Glasshouse score?

Patrick is prodigious. We met at Tribeca Film Festival in 2013. I stalked his website a few weeks later and realized that I’d inadvertently befriended a virtuoso. Since then I’d just been biding my time and hoping our paths would align on a project. Only took eight years. J I created a Spotify playlist of every track I could think of that captured a feeling or tone I wanted in the film, and he listened to that playlist on a drive across country. We traded a few more musical references back and forth, and then he went off and wrote absolute perfection that captured every note I’d hoped for. The whole process almost felt too easy – which is of course a testament to his immense skill and attention to detail.

Can you tell us about the cinematography in Glasshouse and working with Justus de Jager?

We wanted a very distinct look for Glasshouse and Justus was on board with this vision from the very beginning. He immediately got what we were hoping to achieve with the look and devoted himself to making it happen. We were both incredibly excited to be able to shoot on Cooke Anamorphics (thank you Panavision!), as the shallow depth of field and wider field-of-view captures a warped, softer – almost ethereal – view of reality that was perfect for the film. We also used black nets over the lenses to give the footage an almost dreamlike quality: a visual metaphor for a world in which nothing is precisely as it seems. The horizontal distortion on the edge of frame implies the distortion in our characters’ minds. We chose shift-and-tilt lenses for our flashback scenes to represent the unreliability of memory in the film. I wanted these memories to feel like a fish struggling to break free, slipping and jerking in our characters’ minds – hold tight, or lose them.

Handheld work was reserved for the more emotionally fraught moments. As relationships – and memories – are unleashed over the course of the film, Justus’ camera work becomes more frenetic.

We scouted Pearson Conservatory together and Justus figured out how best to design the lighting to achieve the style we were going for despite the challenges of the location. Pearson Conservatory is an incredibly difficult location to light. Since we were surrounded by floor-to-ceiling glass, we were essentially lighting for an exterior location, with the added benefit of possible reflections from all sides. It’s a massive credit to Justus and the lighting team for achieving the look we did on the budget we had, and the film hugely benefited from Justus’ experience in getting that right. He did a remarkable job of realizing the visual vision for the film. He accomplished an amazing amount with very little, which is really the defining quality of an excellent DOP – to be able to capture the desired mood and tone of a narrative despite all the challenges one inevitably encounters on set.

What are your favorite scenes — from on set and in the final cut?

I have quite a few. But in terms of succinctly capturing the relationship dynamic between Bee and Evie, I love the scene where Evie reminds Bee that she can’t trust her memories, and Bee responds that Evie can’t trust her heart. I also love the moment Bee sends Evie off to hang laundry, and the silent looks exchanged. I’m also very proud of some of our more provocative scenes, and those that capture the relationship between Evie and Gabe. They’re as heartbreaking as they are unsettling, and I think Brent and Anja did a beautiful job capturing the complexity of Evie and Gabe’s relationship.

Which films and directors have influenced you as a filmmaker, including Glasshouse?

Long list. Catherine Breillat, Sam Mendes, Todd Haynes, Rian Johnson, Darren Aronofsky, Guillermo del Toro, Agnieszka Holland, Ridley Scott, Jon Avnet, Luc Besson. Can’t really leave out Spielberg or Lucas, either. They shaped a generation.

What are some of your favorite movies from the past decade?

Parasite, Call Me By Your Name, Get Out, Birdman, Tore Tantz (Nothing Bad Can Happen), Mad Max: Fury Road, Moonlight, Looper, Snowpiercer, Arrival, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, The Shape of Water, Ex Machina, Hanna, Raw, The Favourite.

Which themes and subject matters interest you as a filmmaker?

Identity. Perception. Both self-perception and external. Relationships. Sense of self. Truth. Subjectivity. Accountability. Responsibility. To others and the world. Trauma. Coping Mechanisms. Desire. Need. Tragic Flaws. The Past. The Future. The power and influence of memory. Neural plasticity. Human behavior.

Watch Glasshouse