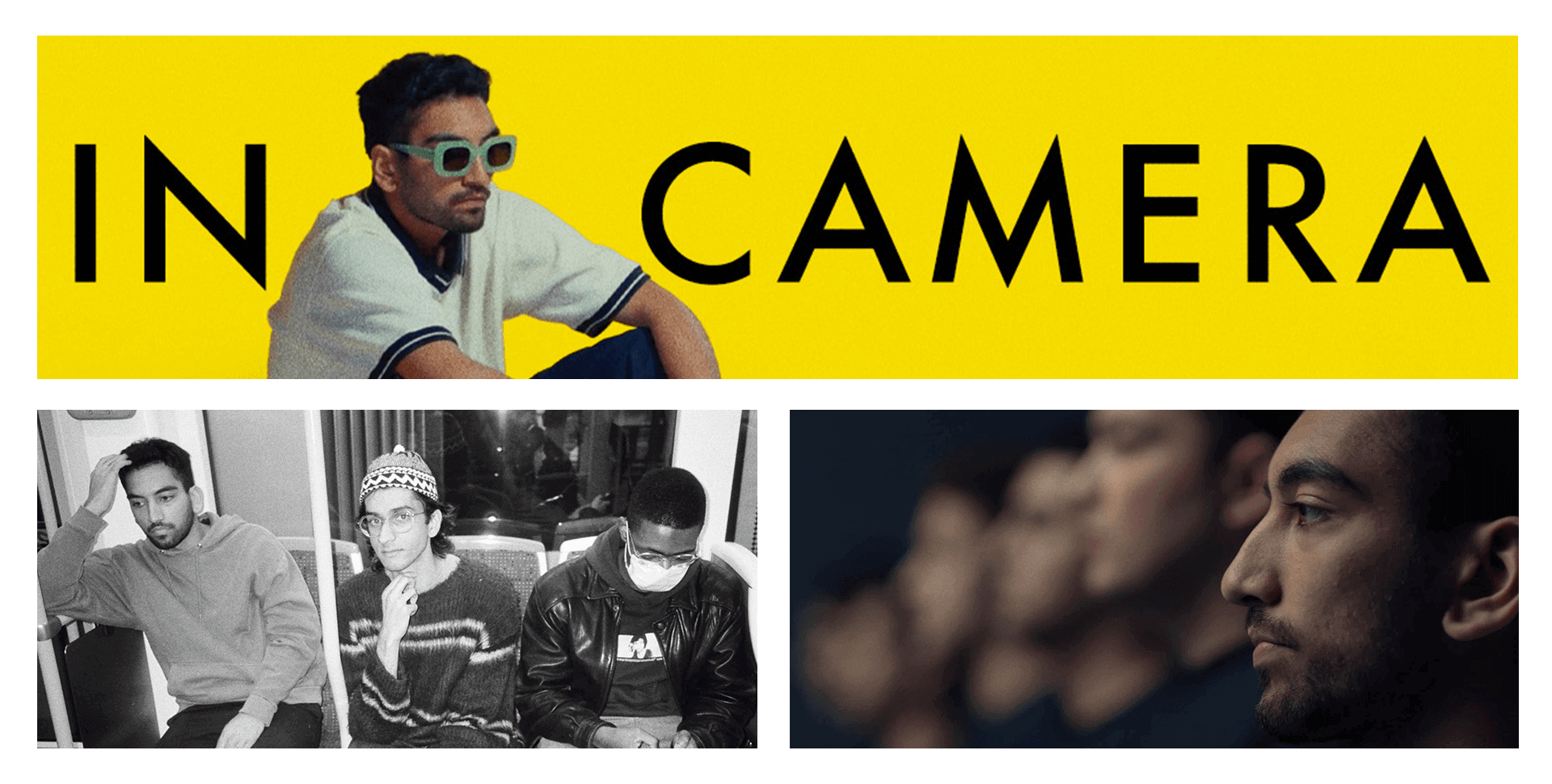

In Camera is a 2024 British drama film that was written and directed by Naqqash Khalid in his directorial debut. The film follows the daily affairs of struggling actor Aden (Nabhaan Rizwan) as he moves from one eccentric audition to the other. His flatmate Conrad (Amir El-Masry) might tell him that "we (brown faces) are the new currency," but Aden navigates himself in a world that's slipping out of his reality. Having recently won a BFI & Chanel Filmmaker Award 2024 by a jury headed by Tilda Swinton, Khalid breaks down his new release, how he got inspired by "the angry young men" of British cinema, and the racial and moral ambiguity of his "alien" protagonist Aden.

The following transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity:

At the screening, you mentioned that you had written the script when you were teaching. You were an academic, and that was when you were 25 when you started writing?

22, actually. It's weird; I should write a sitcom about it, but I did my degree and skipped a Masters, and I started a PhD, and I started teaching at the end of year one, so I was 22. And then, they offered me a permanent job, and I was 24 and 25, so I was doing that for six years, weirdly. Then I was writing alongside that because I didn't go to film school or anything; I didn't have a traditional route. I didn't make any narrative shorts; I made a few art films, I guess you would call them because they were always funded by the Arts Council or Sky Arts. I had no engagement with the film industry, and then I got onto this program called iFeatures, which is what I developed the script on.

But that's what's interesting to me because you, being an industry outsider, and your debut film are so fixated on casting auditions and different kinds of roles. So, how did you get the idea of the story about a struggling actor while you were an industry outsider?

Yeah, I think the role of the actor is kind of the perfect metaphor. There were a lot of things I wanted to talk about when it comes to identity today. I was watching a lot of the angry young men from the British New Wave, and I was just really fascinated by all of those men like Richard Harris and Alan Bates. Even though they're all from different films to me, watching those films very close together, like This Sporting Life, Saturday Night, and Sunday Morning, all of those films. It felt like there was a story that was being told about a generation, and I think there was something really interesting about all of their bodies and how their bodies encapsulated such an anger, and a social story — I think to me, the role of the actor is almost like they're a sociological document, everything that they present and bring with them really holds their time.

So, I knew I wanted to write a fairy tale, and the actor just became the perfect vehicle. But that sounds like a neat narrative — I'm not sure if I was fully conscious of that when I started writing it, but in hindsight, the actor is just the perfect metaphor to talk about all of those things. Because when you walk into a room as an actor, really your race, your gender, what you look like, what you present like, all of that is immediately part of your labor, and how people are going to see you, and what people are going to project onto you — the associations that has. So I think there was so much I wanted to say. I know this for sure: there's so much I wanted to set and critique about neoliberal representation politics. I think the actor was just the best, cleanest in, for me, to have all of this dialogue about what it means to be a young man in Britain today.

In the scene, Conrad tells Aden that "we are the new currency". Yeah, but for me, it's a contradiction in the film. On the one hand, I see Conrad succeeding as well compared to Aden. On the other hand, I see how difficult it is for an actor like Aden, and the only roles he's getting are that of a regular person or that of a hijacker. So, the stereotyping is still there. How do you explain these contrasts — Is there one way of thinking about it? Or is it that some colored person might be succeeding while, on the other end, the other colored person might not be flourishing?

I think what I came down to when I was thinking about these things during the writing process was that the truth is black and brown faces in high places are not going to liberate anybody, you know? These systems are fundamentally not built for us, and I have zero interest in having a seat at the table when the system is rigged. So yes, there will be marginalized people who benefit from these things. I mean, if you look at Rishi Sunak as Prime Minister — does that help black and brown people? No, he's still a white supremacist. Margaret Thatcher, did she help women? These people, I think there is something about, there's something really insidious about marginalized people who, what they have to do to fit into these systems.

I was reading a lot of Frantz Fanon and a lot of anti-colonial literature and thinkers around that. And I think we live in a neoliberal society. The film industry especially loves this. Saying things like representation matters and blah, blah, blah. But all of that discourse is really hollow. I think I was thinking a lot about how we navigate these systems and what we have to do to navigate these systems. How do we make ourselves palatable?

I was thinking very much through all of these quite big political ideas, but they're also part of our mundane day-to-day lives. And I think especially in film and TV, there is this essentialism. When you have one successful person from a marginalized group, they've ticked their box. They have their women director; they have their black director, their brown director. That becomes almost quite suffocating, too, but I'm not sure how to articulate that to you in the best way. To me, this is almost like a horror film about neoliberal representation politics.

So you just mentioned that when a non-white person comes into high places, they get tokenized. Considering that In Camera has been on the film festival circuit since last year, I'm sure you might have received praise from critics or film industry professionals, but were there any moments where even the compliments seemed backhanded? Because not only you're brown, but you're a first-time filmmaker, and you're a young filmmaker. Sometimes, you'll get compliments like, "Oh, I didn't expect that from a first-time filmmaker or a brown filmmaker." — were there any moments like this?

Yes, there are many. You know what? It's really meta. I came into the industry post In Camera, but during making In Camera and putting In Camera out in the world, I often joke that I feel like In Camera happened to me, or it's still happening to me. It's this weird meta experience, and I'm hesitant to give you examples, although there are many. But it is really weird and meta, and it's a bit of a trippy experience, is what I'll say. Sometimes, I'll be in a meeting or be on a panel or something, and someone will say something, and I'll just be like, "I feel like I'm trapped in my own movie." It's kind of crazy, and I wrote this as someone who's, on the outside, detached from it. Having no experience within it. So then, to almost enter it feels meta to me. I don't know how to explain it otherwise. It'd be different if I was in the film industry, a jobbing actor, and then I wrote this about my experiences. But because I imagined all of this and then proceeded to have a lot of it happen to me, [it] is a bit mind-blowing, you know?

In the film, there's a particular scene that stood out to me when Aden is talking to an immigrant cab driver, and he asks Aden, where are you from? And he's like, from here. And then he's like, no, but originally, where are you from? And then, just a series of cuts, and so, we never really get an answer from Aden, so was that racial ambiguity intentional?

Yeah, Nabhaan and I approached Aden as if he were an alien. To me, this is a film about violence, and the first act of violence that I feel like I committed against the character was robbing him of any backstory, robbing him of his own ethnicity or any background about him. In a way, there are lots of reasons for that. I did want to have this alien character who is a bit of a void, but I also think there's something really interesting when people have colorblind casting in movies. When you put someone on screen, and usually a white director pretends that this person is in black or brown, there's something really violent about that. I think I wanted to tap into that almost too and rob this person of any specificity and instead just deal with the external things people would project onto him. I remember early on telling Nabhaan that I think Aden is (not literally), but I think he's kind of an alien. There is that meta moment where he goes to audition for an alien, and she says to him, you have no backstory, blah blah blah, and she's saying all this stuff, and it's so ridiculous — the dialogue, but in a funny way. I always thought that, oh, he's perfect for this.

If you think about Superman, for example. There's almost something about that role that would be more truthful if Superman was black, almost like in an American context — he's taken from somewhere, displaced in this place, and has no sense of his own identity. So there's almost something like about that character. I really wanted to play with that and the idea of that. And I think that just opened up so much more scope for the film. I think I said this during the Q&A. I said this a lot, but I am interested in representing life as it feels, not life as it is, so having that kind of violence against the character by robbing of any specificity really opened up the world in a weird way, and I think it's really sad too. I think there's something really sad about him not having any family, background, culture, or anything. There's something lost and stolen from him, and he's looking for it elsewhere. But I was also thinking if I navigated the world accepting everyone's projection of me, what would happen? And I thought I'd probably go mad, and I put a lot of that into the character.

As much as a film, it's a character study of Aden, it's also, strangely enough, a film about male bonding, and I mean, I could see it in the Q&A as well — when the other actors were talking about the male friendship and bringing it all to screen. But was it always your intention to fill your script with predominantly male protagonists? Because, as you said, Aden has no backstories, or Aden gets no love and trust, and there are hardly any women protagonists in your film. Was that always an intentional choice?

Yeah, completely. When I say things like this is a film about this fairy tale, I really did see this fully as a fairy tale, and choosing to predominantly focus on men and these three men — that was always the intention. This was a film about masculinity in a similar way to those angry young men films; that was the kind of archetype and construction I was interested in. This fairy tale about a man in Britain today, and I think that angry young man construction I was thinking about, what is that today? And to me, that's almost dissolved into the anxious young man. I wanted to have that real, clean precision and focus when making commentary on gender and what it means to be a man today. So yeah, it was intentional not to have any characters that were women. That was intentional, apart from the photographer, who was always supposed to be a woman. And again, in a fairy tale way, she's almost like the prince of the story; she could rescue him, but she seems to have the knowledge, and she had something to say that could almost liberate him, but it doesn't really work out in that way.

Your film has a lot of almost psychedelic sequences, a lot of magical realism and all, which makes sense because, as you said, life as we feel it, instead of as we see it. This one scene that stood out to me was during the haircut scene. It's just these dudes discussing their dreams, which I found to be a very universal scene because there are moments when I get a bizarre dream; I would ask my friend, did you ever get a dream, like bleeding walls? So, what was that inspired from? Was that inspired by your own actual dreams or surreal experiences?

No, I really wanted a tender scene between these two characters and these two characters just talking. Everything is almost with the imagination of Aden, but in that scene, Aden is not present — he almost interrupts the scene. I think there is a real duality with Amir's character. By the end, hopefully, you're questioning if he's even real. He's almost playing two people — he's playing his character, who seems to be a real man who's very present in that scene where he's cutting their hair, who has a backstory, has things to say, exists independently, and has agency. And then, he exists in this other space, which is almost like Aden's imagination. So I wanted a scene where those two characters could exist without Aden, but also just a scene of men talking, and atmospherically, it feeling...yeah, I don't know how to describe it — it's quite unquantifiable. I work in a really unconscious way, too. I do examine everything as a director, but as a writer, I try to be very unexamined. That scene, for example, I was just in the shower one day, and I remember turning to the window. I had my eyes closed, and all of a sudden, I just felt the building is bleeding, and blood is coming out of it, and everyone's looking at me as if to say do something; you're a doctor. I just picked up my phone while still in the shower and typed it in. I never edited a word, and that's what's in the film. I was quite set on: I will not edit this. I just wanted to be as free associated as I'd just written it, and then I never told anyone that. I never told Rory that, and then when the building when we did the blood scene, Rory started doing all this stuff if he was in the shower — I did not tell him to do that. Afterward, I said to him, "Oh, it's really interesting; what were you doing?" He was like, "I don't know, when I read the script and when I was reading it" (he didn't plan this), I just really viscerally felt as if I was in the shower." I think there's just something really interesting about that, but I feel like cinema, especially as a medium, is so linked to the unconscious mind that, as a writer, you should hold space for things to be left unexamined for your own self. I think a lot of the time, especially in a British context, everything is developed to death, where it's like, what does this mean? And then, this leads onto this, and this, this, this. As an audience member, I feel very aware of that. Sometimes I see films, and I feel like they're too well-developed. I want to make a cinema that feels more unconscious, more...

Fluid?

More feral. Yeah, fluid —that's a really great word, and I thought about that a lot. I didn't want it to feel constricted; I wanted it to feel like the film has agency in the film's thinking. I love modernist literature. One of the biggest references for this was Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. I was thinking a lot about Woolf and James Joyce and modernist poets and how they, during a post-war period [and] a really confusing period in Britain, they used their art form to articulate some confusion, but also to try to invent something and to really play with the novel as a form. I think cinema as a form — if you think about it — it's a very young medium still. I think it's exciting as a director to be inheriting this medium, but then being, well what can we do with it? It's not figured itself out yet. Let's just push it and play with it. So, I really want to make films that feel like that, and sometimes some things work, and some things don't, but isn't that exciting?

And I'm glad you mentioned James Joyce and Virginia Woolf because a friend of mine asked because she was intrigued to watch it, but she couldn't come to the preview with me, and she did ask me how the film was, and one of the words that I mentioned was a stream of consciousness.

Stream of consciousness, yes.

Yeah, it's a really stream of consciousness kind of film, and now you're just mentioning Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. Just makes me feel intellectual when analyzing your film.

Thank you so much. That really means a lot that you picked that up because I think that's quite difficult to sometimes articulate. In the edit, Ricardo [Saraiva], who edited this, is such a core key collaborator, and I remember him saying this too. He comes from documentaries, and he was like, you're almost trying to achieve this stream of consciousness thing, and all of your rushes are like that, too. One more thing, my favorite things in the film are I don't say "action" — I like to take the actors into a space that feels like where you're out of your head. I'll just film the band for 15 minutes and then give him brand new words that I've not prepared. I will just be like Nabhaan, can you say, and then I'll just say new stuff, and Nabhaan will also do that. We actually practically worked in a very stream of consciousness way, and then you have to be very specific and craft that in the edit of how to make that feel cohesive. I'm glad that that came across.

Also, one last thing: are you wearing Lacoste again?

I actually am. I didn't mean to. Nabhaan, I think, said this on stage, and it's actually not a joke. I have a PowerPoint of characters wearing Lacoste polos. Yeah. I referenced a lot of my favorite performances. A lot of them have Lacoste polo. I mean, the costume references several performances. Kristen Stewart in Personal Shopper, in every Éric Rohmer film, when they're just walking around Paris in a Lacoste polo, I think there's something really interesting about being in a dialogue with the costume. Costume is a huge part of my process. I think I had the green Lacoste polo, and I had [it] before I wrote the film.

Yeah, and that formed the template of the film for me. Now, when I imagine Aden, I'm always imagining him in green.

Yeah, a lot of those costumes are actually my clothes, too, but all of his work — all of his outfits are athletic. Nabhaan and I are talking about silhouette, so we're talking about rugby silhouettes and football, and all of his outfits are very athletic, so that's also a very Frantz Fanon thing because Frantz Fanon talks about the native being athletic in his dreams because he's so passive in real life.

Watch In Camera