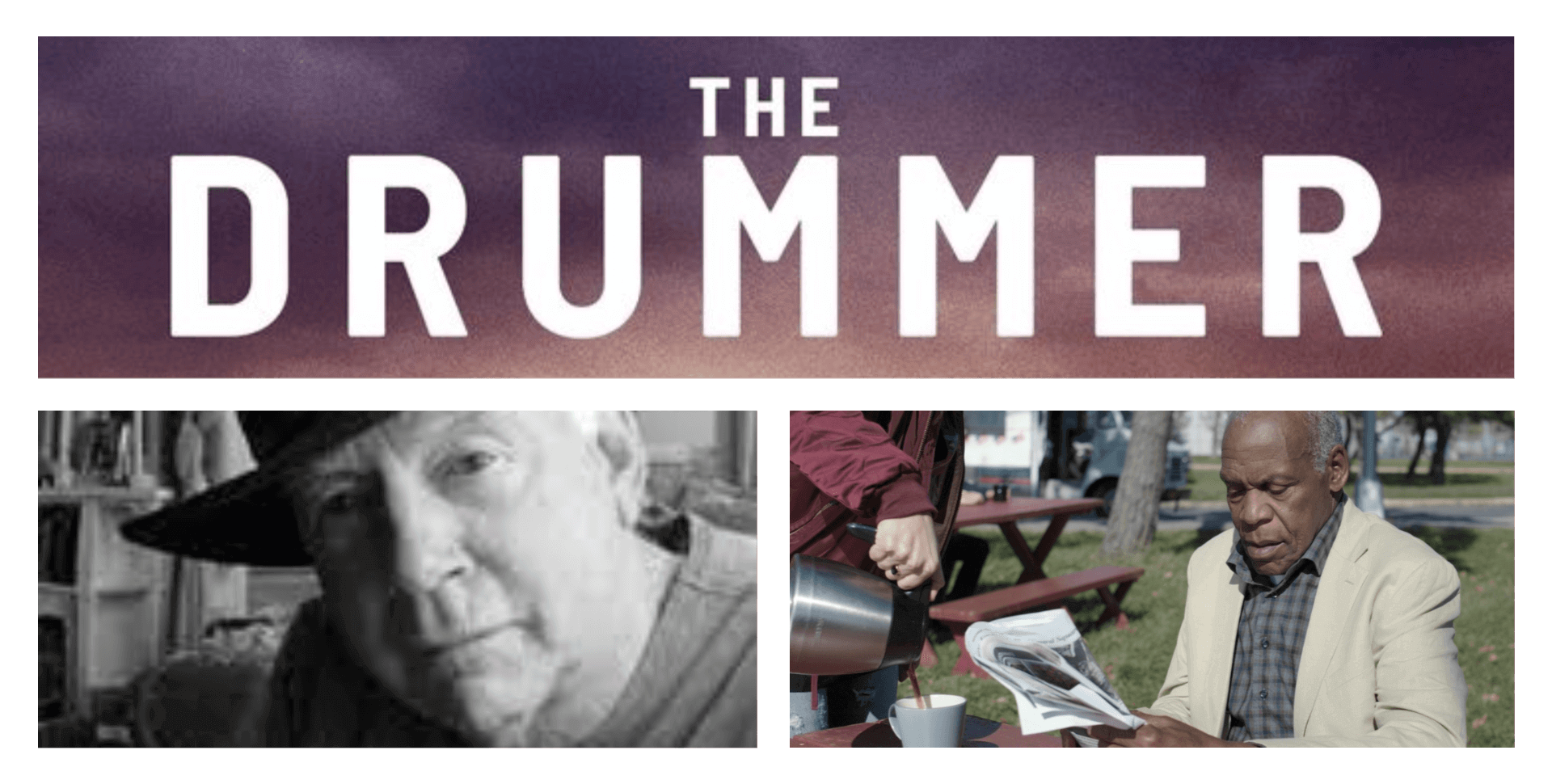

The Drummer is a 2021 drama film that follows a lawyer who tries to help veterans with PTSD. Stars Danny Glover, Sam Underwood, and Prema Cruz.

The director and co-writer of The Drummer, Eric Werthman spoke with Borrowing Tape interviewer Nace DeSanders on various elements of the filmmaking process. The film is now available to watch via VOD and digital platforms now.

Subscribe to 'Behind the Lens' | Filmmaking Interviews @ Borrowing Tape to hear our recorded interviews.

Listen via Spotify, Google Podcasts, Breaker, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, and Anchor.

Listen or read the transcript — edited and condensed for clarity:

Hey movie lovers! I am Nace DeSanders of Borrowing Tape and I am here with Eric Werthman, the director of The Drummer, a social issue drama that brings to light the struggles of American veterans with PTSD trying to be discharged from service. Eric, thanks for taking the time to chat!

My pleasure.

So, to start us off, could you tell us a bit about your connection to the film subject matter?

Well, before I was a film director, I was a psychotherapist for about 25 or 30 years and I made one film about 10 years ago. And then, just as I was winding down my practice, the war in Iraq broke out. I agreed with a group out in Los Angeles to see veterans for free for psychotherapy. And that led to a phone call from an old friend of mine from the 1960s, a lawyer named Tod Ensign, to who the film is dedicated at the end. He was, what was called an antiwar coffee shop. He was a lawyer. He had defended soldiers from the Vietnam period through here to Iraq. And he also was running an experimental antiwar coffee shop up in Watertown, New York. In the sixties, the antiwar coffee shops were set up on Base Towns and were very successful in organizing soldiers who were in the military, but were against the war.

Now I have to admit that this time around it didn't work out that way, probably because in the sixties there was a draft and here in the Iraq war, it was all volunteer. So, Tod was trying to start a soldiers' movement that was antiwar. And he had a few soldiers on the base that he was near Watertown, was near Fort Drum, which was a big jumping-off spot for soldiers going to Iraq. There were a few experiments in anti-war coffee shops around the country. And one was in Texas. One was in Tacoma in Washington. One was in Colorado Springs. And I thought at first that this wasn't going to go, but Tod came up with the idea of having conferences on Base Towns. Well, first just conferences of veterans and clinicians. And then after we had a pilot project in New York, I said, look, we should be doing this on base towns. That's where the soldiers are. So, we did four or five very successful conferences. Alas, Tod then got cancer. And he passed away a couple of years ago and he had all the leads and I couldn't do this by myself. But I had begun to think of an idea for a film based on our experience. And I created a character "Walker" who was a lawyer defending current soldiers, but who also had been an Iraq veteran. And that's how the film grew. I had a co-writer, Jessica Gohlke. We had done a film together about 10 years ago. We wrote it and then we began getting a casting agent and began to move out. And then I met Danny Glover and that's how he got involved in it.

Amazing. That is so interesting. So, then can you explain the film's title, 'The Drummer' to those who haven't yet seen the film?

The Drummer is the name of the antiwar coffee shop. It's based on the old song, "The Little Drummer Boy". And that's why we call the original coffee shop was called The Drummer. And so, I kept that title for people who know that little lyric or that little song, 'a little drummer boy is marching off to war' and that's why the name of the anti-war coffee shop — the real one was called the Drummer. And the one we recreated for the film is called the Drummer.

Wow, that's amazing. So, then what was it like working with cinematographer Marcin Kapron?

It was terrific. I should say that my producer is the head of the new school media department. He's from Belgrade. He's a film director himself. He's done seven or eight great films. Very low budget. Nobody makes low-budget films like he does. His name is Vladan Nikolic and Marcin was a student. He was from Poland, came to the United States, then went back to Poland to go to film school at Lodz [known as the Polish National Film, Television and Theater School] because that's one of the most famous film schools in the world. Then came back to the new school. And I think of a further degree in media studies and he was introduced to me by Vlad. He had shot a little 10-minute film for a friend of mine that was very good. He also turned out to be an associate producer on our film, Julie Deffet — who's from Brussels. And so that's what it was like. I will say that we had some difficulty, we couldn't afford, we didn't have enough money to go up to Watertown in New York, which was a real blow to me and Danny. So, we had to shoot the film around New York City, and it was mostly shot in Staten Island with a few scenes shot in Brooklyn. So, we had to rearrange the shot list literally on the set, because we weren't even sure of our locations until about a week or two before we shot. We realized we couldn't be too fancy. We couldn't spend too much time devising more complicated shots. So, we had to keep it very simple. And of course, there were a lot of closeups. As Danny said, the close-ups really worked for the film, because it made you feel like the characters in the movie, each of them was all alone. They didn't have the kind of community they wanted. They were on their own, and the closeups implied that situation.

Absolutely. You get that feeling from the film, that's amazing. So, what was your favorite scene to shoot?

Oh, dear. Well, a lot of them had to do with my favorite scenes. There's a scene with the fellow, the one soldier who was working with Danny who was an ex-veteran played by Frankie [J.] Alvarez. And they have a discussion in which Frankie asked Danny 'Walker', who was the name of the character that Danny plays, why does he keep doing it? And Walker says that "At my age, resistance is all I have left." And then he says, you know, I should have, in some ways joined the environmental movement, that's what's going on now because as you know, it was very hard to get a mass anti-war movement about the Iraq war. It wasn't like Vietnam at all. And Frankie answers him by saying that's because they think there's hope they're in the environmental movement. So, I thought, we shot that scene outdoors. And that's one of my favorite scenes in the film. I also like the scene when the soldier is arrested with Prema Cruz — who was sensational as Cori and almost steals the movie. She is arrested. And when Walker thought he had set this all up with the base and they betrayed him by arresting her that night I thought the look on Danny's face when he realizes that's happening was just devastating.

The very last scene we shot was a couple of days after we were technically supposed to end. Because we had to raise some more money. Because we ran out of money was a scene in the bar between the soldier who can't decide whether he should get out or stay. And his friend and his wife they're shooting pool. And the friend says, "My wife is pregnant. What should I do?" And Sam Underwood, who plays the soldier, says, "Don't look at me. I'm no hero. I don't know what to do." I thought that scene was really good.

So, what was it like working with Danny Glover? He is absolutely wonderful in this film.

He is. And that was the one great break we had. As you know, as you probably know, when you have a casting director, you draw up a list of actors and we drew up a list of actors who were old enough to have been in the Vietnam War. I was going to an environmental conference — the biggest environmental conference in the United States at the time it was called Bioneers. It was out in San Rafael, California. My wife happened to be on the board of it and so forth. And Danny spoke at that conference on social justice and the environment. And so it was a semi set-up for me to meet him at the lunch and it wasn't formally set up. I had to make my way to talk to him, but I did. And he was really interested in it. It took a couple of months for him to actually read it and that was due to someone in his office.

Danny is very loyal to people he went to high school within the college and a lot of the people who work in his office, he went to high school with. And the daughter of, one of the persons who run the office, had a degree in film production, I think. She read it and said, this is just right for him. And I said, "Can you call Danny and tell him, read it?" And so she called, he was making a movie in New Orleans. She told him, "You should read this." And he called me back in 24 hours. It then took two more years, by the way, to get the screenplay sent. But that's how it happened. And yeah, he was terrific to work with for, he prepared. He thought about it. He made choices on how he was going to speak of the lines. And he is a terrific guy and he is the real thing in this sense that he is a social activist. And so he's out there doing a lot of that kind of work as well as acting.

That is so great. I love that. So, which films or directors have influenced you as a filmmaker, but also the film, The Drummer?

This is a good question in the sense that I'm 80 years old. And I was in high school in the late 1950s. Now my parents took me to see movies. When I was young, they took me to the museum of modern art to see Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. And so I had and my father encouraged me to go see foreign films and art films when I was in high school. But in the late fifties, 58, 59, it never occurred to me quite frankly, that I could be a film director. I mean, growing up in New York, it was Hollywood movies, American movies. And it's just like, that just seemed an unreal world to me. I had no idea how you could get a break into that or get into that. There had been a famous, independent film, John Cassavetes’s Shadows, which I had seen, which grew out of his acting school. And even then, I wasn't sure how you go about this.

And then the New Wave films — the French New Wave films came to New York — Breathless by Godard, 400 Blows by Truffaut, Les cousins by Chabrol. Somehow watching, especially Breathless and 400 Blows, it seemed like one could make movies. Because this was also the introduction of sync sound and it was possible then to make a movie without Hollywood, without so much money. That turned out to be true, but it took me and I tried to break into the movies, but I couldn't get into it in the sixties. And I became an Activist and Therapist. So I came back to the movies late. I was 60 when I did my first film or well, 65, but the movies that influenced me looking back on it — there are four. the very early film is Grand Illusion by Jean Renoir because it was made in the background of something called the popular front, which is when all the left organizations in France got together to fight the Nazis and Renior was very much in favor of the popular front and Grand Illusion has that political ideology in it. Also, it was very class-bound, the famous ending where the German soldiers are about to shoot the two French guys who were escaping from the prisoner of war camp and the two French guys get over the border and just as the German soldiers about to shoot, the German captain hits his gun and says "They made it, the lucky bastards." So it was where the two proletariats, the working class in Germany, the working class in France, where they were together more than who was actually fighting the war.

Then jumping up to the late fifties, I was very much taken with a movie called Ashes and Diamonds from Poland by Andrzej Wajda. This is one of the great movies of all time. I see Martin Scorsese has put down on his 10 greatest lists. And again, it was about a fellow who had fought in the sewers during World War II, but who was not on the communist side, but the nationalist side, which was a brilliant pick by Wajda, because so many Poles could identify with this young kid who couldn't decide whether to continue to fight after the war was over, to go with the nationals and stay with communists. And he goes back and forth. It's one of the great films of all time.

Two other films I like are 'La Guerre est finie' ('The War is Over') by Alain Resnais with Yves Montand was about a soldier who was still fighting the Spanish civil war into the early sixties. And it's devastating to see that film now because they were risking their lives. And then 20 years later, [Francisco] Franco died and suddenly the fascist state just disappeared within six months. And the other is a little film by Godard called 'Le petit soldat' called Little Soldier — which was his second film after Breathless. It's not that well done, very crudely done. But again, it's about a guy who can't decide what political party he's going to be in, but he's being blackmailed by one to assassinate someone on the other side. Those are the four movies. All these four movies have politics at the center of them. And I would say those were the four that influenced me the most.

Wow. That's a really good answer. Those are really good picks.

By the way, I will also say the political, I was a literature major and the novels in the 1930s, André Malraux 'Man's Fate', [Ignazio] Silone 'Bread and Wine', all the novels by Victor Serge, they also influenced me a great deal. And bringing it up into South Africa, Nadine Gordimer's novels were also very important for me to read because they had a political basis. And I, unfortunately, can't think of the other guy who won the Nobel prize. You probably know him. It was, I think one of the novels called Despair.

No, I don't know.

Now he lives in Australia. He and Nadine Gordimer won the Nobel prize and within four or five years of each other, I feel terrible. I can't think of his name. Sorry.

So, what is one idea or a bit of knowledge that you would like audiences to take away from this film, your film, The Drummer?

Well, the one overriding idea, which of course, everyone knows Nace, is that war is terrible and people, if they're not killed or destroyed — either they're re destroyed physically or physically and psychologically. And so the message is, if countries are going to go to war, they better have a really 100% reason for doing this. And as you will, I don't know if you do know, but those of us who were in the anti-war movements felt that the reason to go into Vietnam was very flawed. And certainly, the reason to go into Iraq was flawed. The idea that there were weapons of mass destruction, which turned out not to be true and soldiers' lives were devastated by it. And of course in the Iraq war, women for the first time, now this is a tricky one. And I brought this out in the movie, women were in combat, even though they weren't supposed to be, but the army got away with it by saying that we had run out of men. And we needed a few women who were around. I can't remember what the phrase, the army used, I have it in the movie. But the number of women who were raped or sexually assaulted by American soldiers was very large. So that's almost, I don't want to say that's a sidelight, cause it's a crucial issue. But the point is that the message is, if you're going to go to war you better really have absolute hundred percent reasons to do this to risk people's lives.

Absolutely. And then what are you currently working on any new projects that we should be looking out for?

Well, no. I mean I'm 80 years old. I have an idea. I made some notes, but to be honest Nace, we went into this movie underfunded. Now, this is true about every independent film. In my first film, everything broke right going under. And I was able to do it for a very small amount of money. This film had so many locations and so many more actors that we went into it knowing we were in trouble. We thought we could shoot the film and then raise the money for the post-production afterward, which in some ways it was actually what happened. And I don't know if I can go through that again. I would have to have enough money to make the kind of independent film I'd like to make without all this tension around whether there is enough money or not. So, we'll see. I'll call you if it's coming out if I'm going to do something.