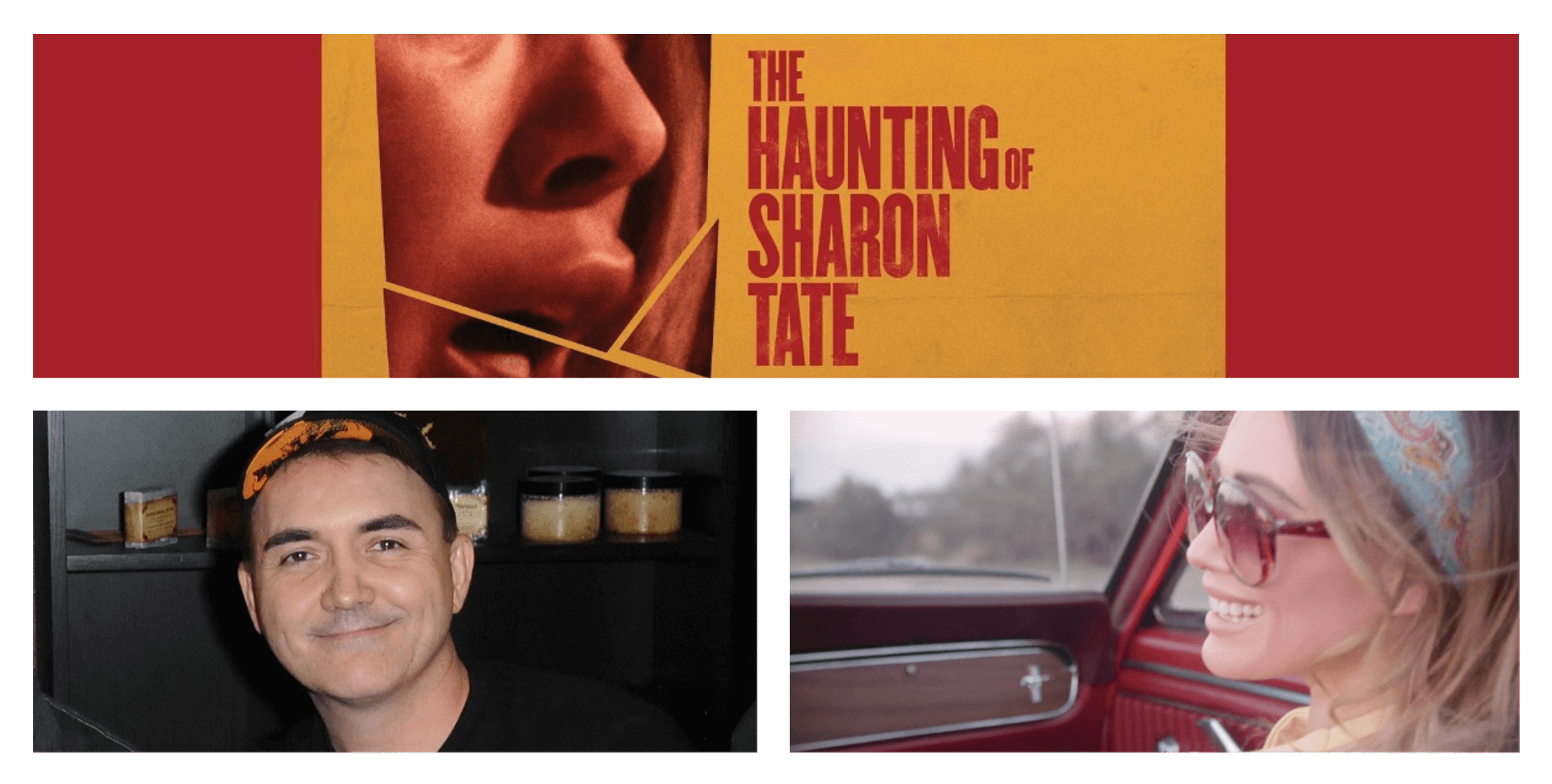

What if Sharon Tate survived that fateful night in August 1969? Writer and director Daniel Farrands explores this idea with his latest film The Haunting of Sharon Tate. Farrands creates an interesting premise based on Tate's premonition of her own murder. He reimagines the horrific event and frames it as a home invasion film with a twist of revenge.

What sparked your interest to tell this particular story? I like that the focus is of Sharon rewriting her destiny, and not an actual retelling of the event.

I was directing my first feature film based on the DeFeo family murders that took place in the infamous house in Amityville, NY, in 1974, and one day while having lunch with Lucas Jarach, my producing partner, I pitched him the idea for making a film that would empower the victims of a senseless real-life tragedy. Undoubtedly, the most famous case of all is the Tate/LaBianca murders of 1969, which also happens to be the year I was born. From a very young age, I remember that “Helter Skelter” and the horrors of the Manson “Family” were still very much in the zeitgeist and it was, frankly, a terrifying time to enter the world and to see all of this through the eyes of a small child. Even as a life-long fan of horror films, and later as a filmmaker, I tended to identify more with the victims in these stories, rather than with the unstoppable killers. For instance, I was much more of a fan of Jamie Lee Curtis’s character in “Halloween,” than I was of Michael Myers. I wanted to tell a new version of the final days of Sharon Tate and her friends but through a completely different lens. Not as a true crime story or re-enactment of the actual events as they occurred, but through a revisionist perspective. I was very much inspired, thematically, by a movie called “Peggy Sue Got Married” from the great Francis Ford Coppola which was actually filmed at my high school in Santa Rosa, California when I was a student there in the 1980s. That film asks the question, “If we knew how our lives were going to turn out, if given the chance to go back and do it again, could we, and would we change our destiny?” When I applied this theme to the story of the Cielo Drive murders, it immediately opened up a path to explore the story from a new, if somewhat more fantastic, angle. I didn’t want to be beholden to all the specific details of the actual crime, because it is just horrible and depressing with nothing redeeming to say at the end. But by presenting this question, and by allowing Sharon Tate to take charge of her own narrative, her own fate, it gave me a brand-new way of exploring these characters, and a way of turning the tables, as it were, on the evil-doers.

As the writer of this film, was it always your plan to direct it as well?

Since I had just come off of “The Amityville Murders,” which I had written and directed, my producing partners on that film and I were looking for other projects that we could get off the ground together. When I pitched my idea for “Sharon Tate,” there was already that immediate “hook” built into the story. I think I had earned their trust enough on “Amityville” to give me another shot, and I am very grateful that they did.

As the director of this film, did you ever critique any of your writing choices? Did anything from your script get lost in translation or left out of the final edit?

I am extremely critical of my own writing. It takes me a while to get into the groove as a writer, and I tend to second-guess everything. I think most writers would say the same. I think when I sit down to approach a script as a director, particularly on these two films which were made on fairly limited budgets and schedules, I was already very conscious about what the limitations were going to be. I tried never to write myself into a corner, or to write things that ultimately would be cut for budgetary reasons. I think having those parameters is somewhat freeing in a way, because you kind of know going in that you have one, maybe two, arenas in which to tell your story, and you have to create your conflicts and drama within the confines of those limited locations and set pieces. I think this holds true on big-budget tentpole movies as well as intimate independent films, but truly your most valuable piece of “real estate” on any set is time. And there is never, ever enough of it. You do your best with the time and resources you’ve been allotted, and you kind of jump in, bust your ass, and hope for the best! That said, there were no big sequences that were left out of the final film. There was a slightly different ending, and some minor pieces of dialogue that were trimmed for pacing and time, but overall we told the story we set out to tell.

How did you get two iconic 2000s stars (Hilary Duff and Jonathon Bennett) on board for this film? What was the casting process like?

Hilary was introduced to us through one of our producers, Jorge Castillo Garcia, and when I met her I was immediately struck by the way her smile lights up a room. She has a certain glow to her as a person, an innate kindness, and that was what I was looking for in terms of the casting of Sharon Tate. Her discipline and skill as a child actor certainly came into play, especially because she was asked to do things she’d never had to do in any role before, and it was a very emotional and difficult part for her to play. She did a lot of research in a short amount of time, and she took the part very seriously and very much to heart. The same with Jonathan Bennett. Fortunately, they had worked together previously so that helped with the on-screen chemistry, but I was very lucky to have found a terrific cast, including the very talented and generous Lydia Hearst, as well as Pawel Szajda and Ryan Cargill. Everyone came together as an ensemble and tried to make it the best that they all could, with a great deal of reverence for the real people they were playing.

The film talks about the idea of predetermination, so the question is: do you believe in fate? That our stories are already written. Or do you identify with what Jonathon Bennett says about altering your story, of having agency?

I think that’s one of the great mysteries of human life. Who are we? Why are we here? Do we have souls, and if so, do those souls live on after our physical bodies have expired? Having had a few experiences of my own that I can’t quite chalk up to mere coincidence, I do believe that there is something beyond the physical realm we inhabit. The optimist in me wants to believe that we have free will and that we are not slaves to any kind of pre-ordained destiny. I think there is strength in believing that because I think we are all capable of becoming more than what others think of us, or what we have been told our station in life should be.

What are you excited for audiences to take away from this film?

Undoubtedly we are treading on sacred ground simply by telling a version of this story. It’s one that gets under people’s skin, and still (pardon the pun) haunts us fifty years down the road. I hope if audiences come away with anything, it’s that Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Steven Parent, and Wojciech Frykowski were real people with real lives and real hopes for their future. And that their lives were tragically cut short during a night of inexplicable and insane violence. I hope by approaching the story in the way that I have, people remember them as heroes, rather than hapless victims. I think that theme resonates powerfully in an age when victims are finally standing up to their aggressors and being given a voice. I believe all victims, whether or not they are still alive, deserve to have that voice too. I think as storytellers we have the ability to rewrite some of the most terrible and tragic wrongs throughout human history, and I suppose in some small way, my approach to this story was my attempt to do that.

The Haunting of Sharon Tate is releasing soon, as well as The Haunting of Nicole Brown Simpson later in the year. Will we be getting an unofficial haunting trilogy?

I’m not sure just yet. It would be great to tell another story to complete a “trilogy,” but that was never the intention going in. I just wanted to approach these stories from a new angle, and to tell them in a way they haven’t been told before. For every Sharon Tate and Nicole Brown, there is a Jay Sebring, a Steven Parent and a Ron Goldman, whose names were overshadowed by the fame (and notoriety) of other, more famous people. I hope in some small way these films pay tribute to those people as well.

If you had an infinite budget and unlimited resources, what project would you bring to life?

Gosh, I don’t think there is any director who has ever been given an “infinite” budget but it would be great to be able to make a movie in more than 15 days! That said, I think some of the best movies ever made have been born out of passion and instinct more than unlimited budgets and resources. Money does help you solve some problems, but if the story isn’t there, to begin with, and if the people involved aren’t passionate about making it the best it can be, it doesn’t matter if you have $100,000 or $100 million. To quote someone much more learned than I, “real art is in the doing of it.”

Lastly, what’s next for you?

I just finished a pilot based on a very famous horror title that I am getting ready to shop around, as well as another feature film we are hoping to make soon about Thomas Edison’s fascination with the occult. I’m also up to direct an episode of a horror series “reboot” that would be a lot of fun to do.

The Haunting of Sharon Tate is showing in select Theaters starting April 5,

and is available to watch On Demand now.

Watch The Haunting of Sharon Tate via iTunes or while it's showing in a cinema near you.